Sourcing fuel and maintenance services (in-house or outsourcing)

Sourcing fuel

The way fuel is purchased for operations will vary widely. In certain contexts, it is widely available through standard commercial services such as filling stations, but in other contexts it is less widely available and is distributed through local traders and networks.

Procurement of fuel

Like any other commodity or service, fuel must be purchased following the applicable procurement, fraud and corruption and counter-terrorism policies. However, due to the importance of fuel to the success of the operation, it usually requires more control than the procurement of other items or services after it is purchased. Both the quantity and the quality of the available fuel must be monitored closely.

Where possible, at least one contract should be in place to ensure the supply of fuel – multiple contracts will mitigate the risk of shortage.

The contract(s) should detail the expected quality of the fuel provided, and supplied fuel should be checked regularly against agreed quality standards (by an independent laboratory if necessary).

Where contracted suppliers cannot supply fuel, alternative options can be explored, in which case the purchase must follow the applicable procurement policy. For example, where a supplier has been contracted but is facing a one-week shortage, the fuel for that week must be purchased through the applicable procurement process, determined by the cost of the estimated total amount required for the week.

Fuel suppliers’ performance must be closely managed, and periodic contract reviews are recommended due to the criticality of fuel availability.

Fuel purchasing cards

In urban contexts, fuel purchasing cards are widely available. These cards are usually connected to an online platform, through which the fleet manager can track consumption.

Fuel cards can be pre- or post-paid, and they allow drivers to refill vehicles without having to request cash. Fuel refills must still be recorded in the logbook, and receipts must be kept for traceability and reconciliation purposes.

Fuel purchase vouchers

Where filling stations cannot provide purchasing cards, the recommends the use of fuel purchase vouchers.

Each vehicle should have a purchase voucher booklet in which drivers can record fuel purchases. Each voucher must have a unique number, which should be recorded by the fleet manager.

The fuel purchase vouchers must be signed by the driver, the filling station attendant and the fleet manager, with copies kept by all parties.

At the end of the month (or of a pre-defined period), the filling station can issue an invoice against all fuel purchase vouchers in the period. The fleet manager must then reconcile the vouchers against his own records (including the vehicle logbooks).

Fuel deliveries to point of use

In other contexts, fuel may need to be delivered periodically to one or several operating sites.

In this case, the delivery site must ensure that storage facilities are available to safely stock and issue fuel (an isolated, locked storage area only for fuel, equipped with fire extinguishers and sandbags, permanently staffed and with ideally only one staff member issuing and reporting on fuel distribution, and proper fuel issuing equipment).

Having the right refuelling system, with fuel vouchers and proper approval scheme in place under the supervision of the fleet manager, is critical in this context, to ensure consistent consumption control see the Daily checks on vehicles and generators section.

Where fuel is delivered directly from a supplier, they should provide a set of documents including certificate of quality, certificate of origin (especially if fuel is imported) and delivery note.

Fuel should be sampled and tested, ideally on site. Fuel testing does not require sophisticated equipment; a used fuel filter and a tube of Kolor Kut water finding paste are often enough to detect dirty or water-cut fuel. Kolor Kut paste should be smeared on a dipping stick, which is then plunged into the fuel container for two seconds. If the colour of the paste changes, the fuel contains water. Other brands of water-finding paste work in similar ways.

Sourcing maintenance services

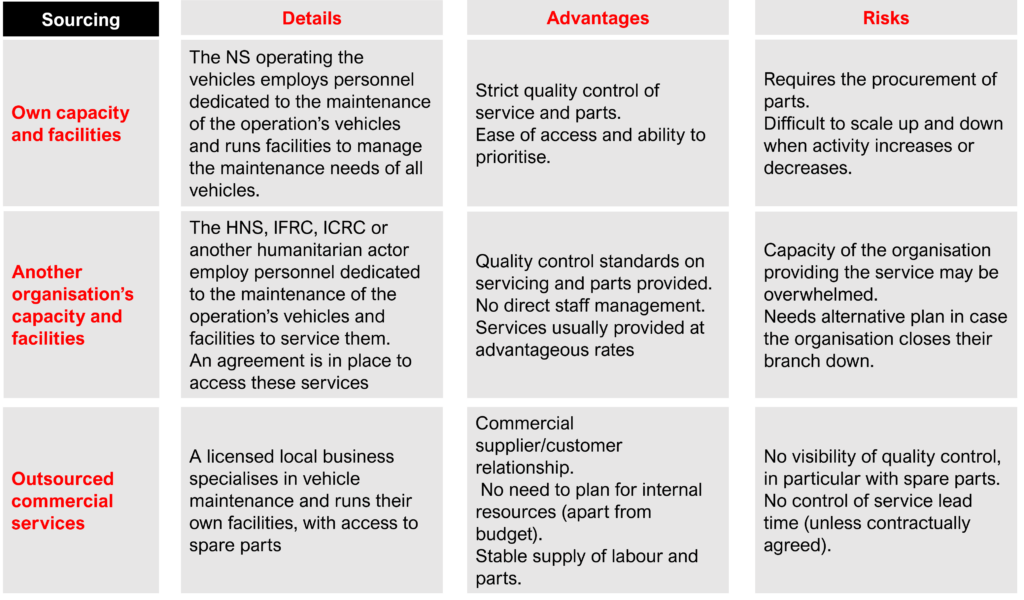

Depending on the context of the operation, maintenance services can be provided in different ways. Each presents advantages and risks:

Available to download here.

Where maintenance services are outsourced, they should be sourced through the appropriate procurement process. Ideally, a contract or framework agreement should be in place with at least one service provider, detailing a service level agreement and performance management principles.

Vehicle and driver schedules, generator running hours

Vehicle and driver schedules

Office hours drivers must work in accordance with local legislation regarding working hours and length of duty. Drivers should ideally be assigned to a single vehicle, to ensure traceability and accountability of resources.

In locations where no personal or public means of transportation are available, a duty driver system can be implemented to provide transport services outside of working hours, within a designated area. This ensures that delegates have means of transportation outside working hours.

Duty drivers should remain on standby for designated shifts in evenings and at weekends. recommends:

- Minimum of four drivers available (each covering a six-hour shift, for 24-hour availability – consider security procedure for evacuation in specific contexts.

- Minimum of one vehicle available for each duty driver.

- Means of communication must be available for the duty vehicle/driver (either a VHF handset or mobile phone, depending on local phone coverage).

Duty driver allocation should be based on a rotation system and in line with local labour law.

Generator running hours

Just as logbooks track usage of vehicles, a generator’s running hours must be monitored, to ensure regular maintenance and follow-up regarding consumption.

A generator logbook should be available for each generator in use, tracking the number of hours it is used, maintenance services and refuelling (time, date and litres).

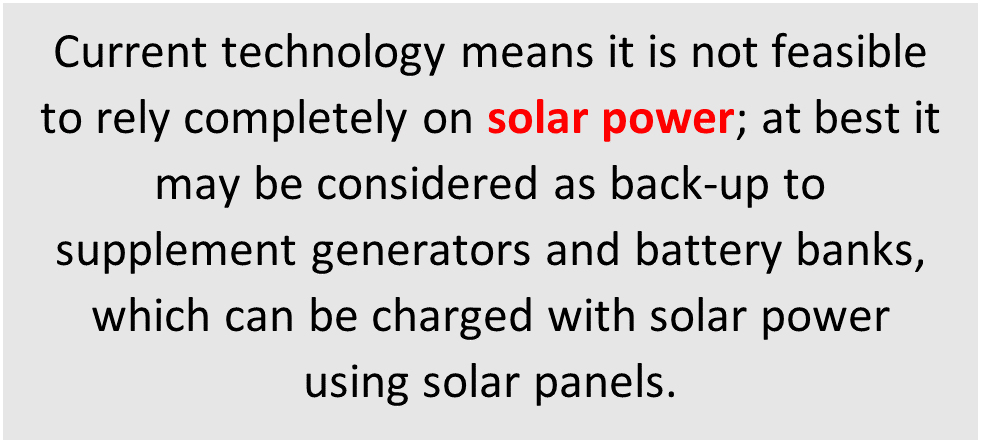

In operations that rely on generators to provide more than 50 per cent of the electricity requirements, it is recommended that the use of generators is alternated either with batteries (which can be charged by the generator when in use) or with spare generators, to limit wear and tear, allow for rest periods and guarantee back-up in case of servicing or breakdown.

Daily checks on vehicles and generators

Daily checks on vehicles

With all vehicles, it is usually the responsibility of the driver to carry out the necessary checks. Ideally, a daily inspection checklist should be available for the driver to fill out, but verbal follow-up or a note on the vehicle logbook can be sufficient in smaller operations.

The minimum daily inspection should be based on the FLOWER technique:

F – Fuel: fuel level must be checked.

L – Lights: all lights to be checked.

O – Oil: check oil level when engine is still cold and vehicle is parked on a flat surface.

W – Water: check the coolant level and top it up with coolant or water if level is low. Do not mix anti-freezes. Check the screen wash reservoir.

E – Electrics: check the battery is safe and secured in its place.

R – Rubber: check tyre pressure (finding the recommended pressure either in the vehicle manual or on the frame of the driver’s door), uneven wear, side wall damage and tread depth (check the tread indicator on the tyres).

A FLOWER diagram is available to download here. A more detailed vehicle inspection checklist is available to view and download here.

Daily inspections on generators

Like vehicles, generators should be inspected daily and any defects should be flagged as early as possible.

View and download a generator inspection checklist here.

Following fuel consumption

Taking stock of fuel

As the volume of fuel fluctuates depending on ambient temperature, the use of metric tons (MT) is recommended as the unit of measure for ordering, receiving and taking stock of fuel (fuel issued can be recorded in litres but quantities should be included in metric tons for stock taking).

To avoid discrepancies, use a calibrated, non-metallic dipstick.

For fuel stock takes, a temperature correction of fuel volume calculation table exists to advise how to adjust the fuel quantity according to temperature.

Where the fuel is managed by the organisation at the operation’s level, fuel stock reconciliation must be made across fuel requests, vehicle logbooks, fuel deliveries and by a physical count. Where fuel is purchased directly from filling stations, no stock take is required, but invoices must be reconciled against logbooks and receipts.

Monitoring fuel consumption

A variety of tools is available to monitor fuel consumption:

- where fuel cards are in use, reports can be provided by the supplier

- fuel request vouchers

- logbooks

- fleetWave system (where available).

To calculate fuel consumption, use the below formulas:

For vehicles:

Consumption = litres consumed ÷ distance covered (km) x 100 = XXX litres per 100 km

For generators:

Consumption = litres consumed ÷ hours operated = XXX litres per hour

Generally accepted consumption rates can be found here.

-based logistics coordinators or regional fleet managers can support the analysis of variances if needed.Maintenance planning and tracking

Ensuring the proper maintenance of fleet reduces the risk of accidents, and of damage or loss of goods handled by logistics and delays to the delivery of items.

The importance of preventative maintenance

Preventative maintenance encompasses all actions taken to prevent vehicle failure. Regular maintenance where vehicle and generator parts are lubricated, adjusted, tightened, or otherwise checked will prevent most of the common mechanical failures. Preventative maintenance guarantees staff safety, while also saving time and money.

Benefits of preventative maintenance:

- Vehicle condition is under control and any misuse is flagged at an early stage, avoiding damage to the vehicle.

- All deficiencies in the vehicle condition can be corrected at an early stage.

- Adjustments and repairs can be carried out easily.

- Time needed for repairs is shorter.

- Costs of repairs are lower.

- Need for major repairs is less frequent.

- There will be fewer unforeseen breakdowns of the vehicle/generator.

- The equipment’s lifecycle will be lengthened.

Planned maintenance

The fleet delegate or manager must ensure that all vehicles and equipment are maintained and serviced according to instructions in their user manuals.

All vehicles should carry and maintain up-to-date records of maintenance, including a maintenance schedule. Drivers or other users of fleet must inform the fleet manager of planned maintenance on the equipment they are responsible for.

The fleet management system allows the tracking of maintenance history and planning. Where FleetWave is not in use, this information can be kept in the vehicle file or on a vehicle follow-up spreadsheet.

Service schedule

Below is an indicative table of recommended maintenance milestones. Local regulations may require a stricter maintenance schedule and it is not uncommon for governments to require maintenance records to be kept on file for a number of years.

| Type | Maintenance milestones |

|---|---|

| Light vehicles | Every 5,000km (10,000km maximum) or 18 months |

| Heavy goods vehicles | Every 15,000km or 18 months |

| Motorcycles | Every 10,000km or 12 months |

| Handling equipment | Every 250 hours |

| Generators | Maintenance (including oil and filter change) every 100 hours |

Engine oil should be replaced every 10,000km, depending on the quality of lubricants in use.

Unplanned maintenance

Planned maintenance should ensure that unplanned maintenance is required as rarely as possible. However, where a malfunction is reported by a driver or other vehicle user, usually following usage or a daily check, unplanned maintenance may sometimes be required immediately, leaving the vehicle unavailable for the duration of the service.

Defects or malfunctions should be reported through a maintenance request form, signed off by the requestor, the fleet manager and the budget holder (usually the logistics delegate or programme manager) and logged in the vehicle file or on a follow-up spreadsheet.

Where no logistics staff are available, country representatives/delegates should seek support from / or logistics coordinators to advise on maintenance requests and cost recharges.

Incident reporting

All incidents involving British red Cross staff must be reported – refer to the British Red Cross incident reporting procedure for further information.

Where delegates are seconded into another organisation such as the or the , or where they are working under another organisation such as a , this organisation’s incident reporting procedure must be followed in parallel to that of the British Red Cross.

Reporting on fleet

Managing and reporting on fleet performance is an important component of operations management. Where it is in use, FleetWave can produce monthly performance reports, but this requires disciplined submission of source data. For more information about using FleetWave, contact the -based logistics team or the global logistics services team in Dubai.

For information on calculating basic fleet performance, see Fleet productivity: utilisation and performance and Monitoring fuel consumption sections.

Other important indicators of fleet performance may include:

- environmental impact measurement

- total cost of ownership

- benchmarking against other fleet options (, rentals, etc.).

The Fleet Forum has developed performance-measuring tools that cover these indicators, among others. The group has also proposed a fleet management reporting format, which supports monthly data collection and analysis.

Fleet performance can be reported as part of the logistics monthly report, or separately where the fleet size is more than 30 vehicles and where a fleet manager oversees a dedicated fleet department or team.

Read the next section on Fleet disposal options here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Available to download here.

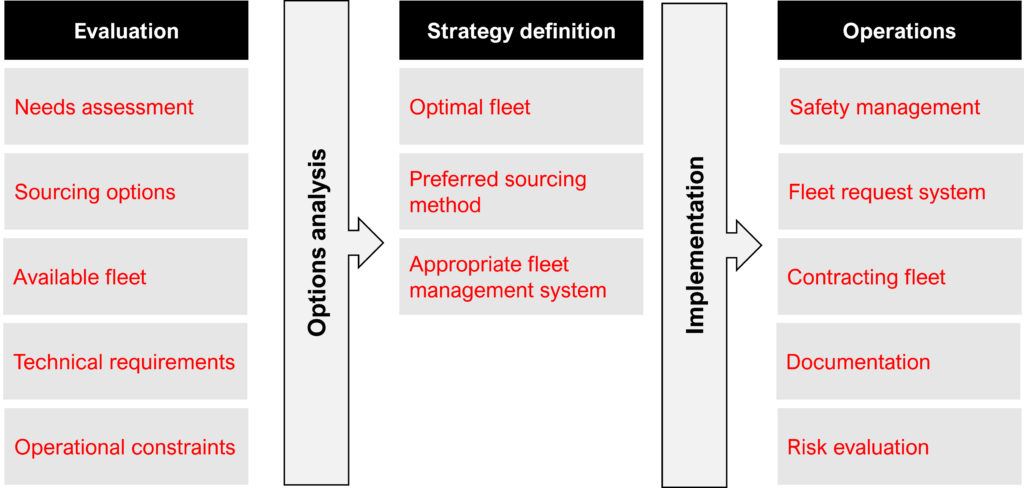

Note: operational constraints include security context and regulations that may apply (import options, labour law, etc).

Vehicles

The number and type of vehicles should always be aligned to the operational needs and conditions, including security, terrain, and team movement patterns. Operational fleet decisions must be compliant with safety and security guidelines (as stated in the IFRC Fleet Manual), with any deviation requiring approval from .

The vehicles selected must comply with IFRC standards, unless approval for the use of non-standard vehicles has been obtained from UKO.

When selecting vehicles, consideration should be given to the following factors:

- local terrain and topography

- state of road and traffic infrastructure

- need for specific equipment, such as in-vehicle communications equipment, a tow-bar or winching equipment, or use of the vehicle as ambulance

- import and export regulations

- local driver capacity (automatic or manual driving, 4×4 driving, left or right-hand drive)

- distance to be travelled and estimated usage (frequency, payload, etc)

- compatibility with existing fleet composition

- local and national service/maintenance and the availability of spare parts

- local rules and regulations, including emission regulations (not all IFRC-standard vehicles meet current emission levels for all countries)

- climate, including seasonal change.

The IFRC standard products catalogue contains full technical specifications of Federation-standard vehicles.

The key point for organising fleet is knowing what the needs are for the programmes in the country office (including any sub-delegations) and for general operations. It is the role of logistics to analyse these needs and then optimise the fleet. This, combined with the national regulations (i.e. load limits for trucks) and the limitations of the surrounding area (i.e. infrastructure) will provide the necessary information to choose the most effective set-up of fleet.

Defining the number and type of vehicles depends on the volume of the workload and the material or number of passengers to be transported, as well as the distance and terrain covered.

The below table will help define the type of equipment needed in operations. To help calculate the number required of each type of vehicle, see Annex 9.1, vehicle set-up evaluation in the ICRC fleet management manual.

| Consider | Criteria | Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Type of terrain | Town/country/topography Paved/dirt roads Seasonality Warehouse Construction site | Cars, high-range 4x4, low-range 4x4, engine power Specifications of vehicles Tyres, sand plates, motorbikes, etc. Forklift Digger |

| Transport capacity | Bridge and road weight restrictions Local/international distribution Transport of passengers/cargo | Light trucks Trucks Bus |

| Radius of operation | Vehicle fuel capacity and reliability Number and type of vehicles Typical and exceptional journey durations Fuel quality and quantity in area of operation | Refuelling options, linked to typical and exceptional journeys (mileage and duration) Fuel sourcing strategy Storage on site |

| Availability of electricity | Power for all operations Security | Generators vs city power |

Each department has its own needs in terms of type and number of vehicles to add to the fleet list. For example:

- Administration may require cars for errands or official visits.

- Programme teams may need light 4×4 vehicles for field visits and transfers.

- Construction and warehousing teams may need pick-ups for equipment.

- Teams in charge of distribution (usually called relief team) will need trucks.

Combining and analysing these needs into a summary table will help constitute the fleet (in number and type), in a way that meets the needs of each team and minimises the cost of operation. The vehicle pool system (see the Requesting a vehicle and cost recharge section of Vehicle usage) should be considered, as it maximises vehicle utilisation through avoiding the taking of vehicles without justification.

| Team 1 | Team 2 | Team 3 | Team 4 | Team 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle type 1 | ||||||

| Vehicle type 2 | ||||||

| Vehicle type 3 | ||||||

| Vehicle type 4 | ||||||

| Total |

Available to download here.

Power supply

Generators must be set up and maintained by qualified staff – a mechanic or a head driver. Support is always available from locally available staff from other , or or from -based logisticians.

Note: specialist skills are required to manage generators. Staff involved in plant management processes must be trained electricians or experienced logisticians.

The output of a generator is measured in KvA (kilovolt-ampere) and volts. They can be air or water-cooled and can be soundproofed (silent) or not. Generators are either petrol or diesel-powered.

The British Red Cross uses hybrid generators when deploying their logistics or Emergency Response Unit teams (see the ERUs chapter for more details on the ERUs). These provide standard power generation and simultaneously charge a set of batteries, which can be used to provide power once the generator is turned off. The batteries’ power demand must therefore be included in the load calculations. Details of the generator specifications as well as a user manual are available from the international logistics team upon request and provided to the teams when they deploy.

It is important to match the power generated to your electrical needs as closely as possible: if the load is too high, the generator will stop and be damaged. But when the generator is supplying less than 40–50 per cent of its power capacity, fuel consumption increases, the lubricant deteriorates more quickly, and the engine’s life cycle is reduced.

Without any power demand to it, a generator will typically already be using 25-30 per cent of its rated power.

| Scenario | Impact on generator set | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Power demand is less than 40–50% of the maximum rated power | Fuel consumption increases Generator life cycle is reduced Lubricant deteriorates more quickly |

| B | Power demand is between 60–80% of maximum rated power | Optimal use of the generator |

| C | Power demand is more than 80% of the maximum rated power | Fuel consumption increases (but less than in Scenario A) |

| D | Power demand is more than 100% of the maximum rated power | Generator stops Generator life cycle is reduced |

Available to download here.

It is a good idea to have batteries as part of an electricity provision setup, so that they can be charged while the generator is turned on. Critical appliances (communication systems, fridges, alarm and/or security systems) can then work in case neither city power nor the generator can supply power. If the generator is used to charge batteries, make sure their rated kVA is calculated into the total power requirements.

To calculate your power supply needs and to choose the right generator, use the power calculator table. The generator size (in kVA) must be equal to or greater than the total consumption of all appliances. The higher starting requirement must be considered when calculating the generator size.

| Consider | Criteria | Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical load | Total load calculations Power (kVA) Local voltage and frequency | Reduce requirements? Alternate generators? (consider whether budget can cover duplicate setup) |

| Expected usage | Permanent/back-up system Consider requirement for UPS by way of back-up Starting system (manual/electric/automatic) | Alternate generators if constant power supply needed Establish running hours with regular breaks (consider if budget can cover duplicate setup) |

| Make, brand, place of manufacture | Local availability and quality of relevant fuel and parts Local maintenance capacity | Budget for fuel and spare parts |

| Geographical area of use | Altitude Temperature and weather conditions Exhaust emission regulations Cooling system (air/water) | Improve electrical safety at location Isolate generator appropriately (consider budget availability) |

| Place of use | Indoors/outdoors Ventilation Protection from elements Noise and disruption Type (portable/fixed/on trailer) Safety | Budget for generator shelter or noise reduction system Require inspection of terrain Security requirements How to earth it effectively? |

| Price | Budget, set-up costs, maintenance costs | Within budget/out of budget |

Available to download here.

Fleet options and modalities

The ’s aim regarding fleet management is to standardise fleet as much as possible, allowing for easier tracking, resource-sharing, and maintenance management. It also allows different parts of the Movement to benefit from competitive pricing from manufacturers.

Vehicles outside the list of standard fleet should only be purchased after approval from a centralised fleet management team (usually HQ logistics, or ).

The IFRC standard products catalogue and include the list of standard vehicles.

Fleet to be used in field operations should always be procured centrally and through the existing agreements with manufacturers.

Where fleet is being procured locally and only for city use, the following criteria should be adhered to as much as possible:

- Make – well-known European or Japanese make, well represented in country of operation.

- Category – city car (Peugeot 208, Toyota Corolla or equivalent), not necessarily a station wagon.

- Engine power – maximum 100 hp or 75 kw.

- On-board security – Alarm/immobiliser, antilock braking system (ABS), electronics stability control and air bag if available.

- Fuel – diesel or petrol (check regulations, availability and consider the environmental impact).

- Pollution control – optimum, but at least as per local regulation.

- Transmission – two-wheel drive, preferably automatic – unless road conditions in the city require four-wheel drive.

- Colour – preferably white, and a light colour if not available – should not clash with Movement visibility.

- Budget – equivalent to the cost of standard vehicles.

- Maintenance – access to local maintenance without HQ support.

Standardisation and compliance to environmental regulations should also be applied to the choice of generators. In general, ensure that the brand is well-established, that fuel type matches local fuel availability and that spare parts and maintenance are widely available.

Different types of fleet sourcing solutions

British Red Cross own fleet

In this option, the British Red Cross purchases the vehicles and uses them for its operations.

The decision of what vehicles and how many to buy will be based on operational needs and the procurement must be controlled and managed through . Such vehicles would be purchased and imported under the and the British Red Cross would donate the vehicles to them once the British Red Cross-supported programme ends.

This option would usually only be considered when:

- it represents better value for money than other options, such as using the ’s system

- vehicles are required for more than two years

- there is assurance that the donation does not place an unnecessary burden on the HNS in terms of maintenance and cost.

In these cases, the British Red Cross usually covers all the costs associated with the vehicles, including maintenance, drivers’ charges including per diems, local insurance, registration and fuel.

The maintenance of British Red Cross-purchased vehicles outside the UK is done following the IFRC maintenance guidelines, unless it is agreed that the vehicle is managed under the ‘ fleet management procedures.

Commercial rentals

Renting vehicles or outsourcing their maintenance can be a requirement for an operation either temporarily (during a short-term surge in activity) or as a long-term solution (where ownership is not an option).

If renting vehicles, the applicable procurement procedure should be followed. The selected rental company must be reputable and offer value for money. See the Sourcing for procurement section for more details.

IFRC vehicle rental programme

For step-by-step guidance on sourcing vehicles through the , refer to the VRP service request management/business process document.

The vehicle rental programme

The International Federation’s vehicle rental programme (VRP) was established in 1997 to ensure a cost-effective use of vehicles and fleet resources. Revised in 2004, it continues to be an effective means of providing vehicles to International Federation and National Society operations. The programme is run as a not-for-profit service within the International Federation; monthly vehicle rental charges are calculated to cover the vehicles and the operating costs of the VRP.

Depending on the estimated period of vehicles’ requirement, it may be cheaper or more straightforward to rent them through the VRP, but a full cost comparison should be done before a decision is made. Cost comparison must cover the cost of the vehicle, shipping, registration, insurance and local insurance, maintenance and PSR of 6.5 per cent.

The overall aim of the VRP is to provide good-quality vehicles as quickly as possible, and with maximum bulk discount. It also enhances standardisation, centralises control and minimises costs, through end-of-lease sale. Vehicles on this programme are managed through the fleet base in Dubai and remain the property of the . All leases must be organised through the IFRC.

The vehicle rental programme is managed through the global fleet base in Dubai, but a lot of the fleet management team’s responsibilities are delegated regionally and implemented through regional fleet coordinators in the Operational Logistics procurement and supply chain management units (OLPSCM, also known as Regional Logistics Units).

Note: monthly VRP invoices are processed through .

The VRP agreement is materialised through a vehicle request form, which must be signed off by the British Red Cross country manager and submitted to the global logistics service (GLS) team in Dubai.

Global fleet base vs regional units: roles and responsibilities

VRP system – roles and responsibilities are as follows:

Global fleet unit (Dubai)

- overall management (operational and financial)

- maintaining the VRP business plan

- procurement hub for vehicles and vehicle-related items

- managing all incoming requests for dispatch and allocation of new and used vehicles

- supporting disposal of VRP vehicles

- preparing vehicles for deployment (technical assessment and repairs).

Regional fleet coordinators (in )

- implementation and maintenance of standards at a regional level

- advise on the implementation of preventative maintenance and repairs to maximise lifespan and usage of regional fleet

- coordinate movement of fleet across the region

- supporting planning of transportation needs in the region

- implementing standard asset disposal procedures

- ensuring proper maintenance of fleet wave database and analysing data

- reporting on regional fleet usage to global fleet base

- maintaining regional fleet files

- advise and train on fleet sizing, fleet management and VRP

- managing regional IFRC fleet.

VRP rental costs

To encourage forward planning, cost incentives have been built into the . Rental rates are based on a sliding scale, in which longer rentals benefit from cost savings (i.e. a sliding scale, based on the duration of the contract).

| Model | Five-year average monthly cost (CHF) | 12-month average monthly cost (CHF) |

|---|---|---|

| Toyota Land Cruiser HZJ78 | 720 | 830 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser pick-up double cabin HZJ79 | 671 | 775 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser pick-up single cabin HZJ79 | 650 | 750 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser SWB HZJ76 | 736 | 850 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser Prado LJ150 | 696 | 800 |

| Toyota Corolla ZZE142 | 635 | TBC |

| Toyota Hiace minibus LH202 | 621 | 715 |

| Nissan Navara pick-up double cabin | 546 | 630 |

Available to download here.

These rates are indicative and may change – quotes can be requested from the global fleet team when considering renting vehicles through the VRP. The latest version of the rate sheet is available here.

An additional 6.5 per cent programme support recovery cost must be added to the total cost of the contract with the VRP, as well as delivery and return shipping costs (including any applicable import duties).

VRP system – cost structure

Included in VRP rental rate

- global third-party liability insurance cover (up to CHF 10 million)

- full vehicle damage insurance (including a replacement vehicle)

- vehicle replaced at the end of its lifetime

- fleet management support

- accident insurance for driver and passengers

- specialist driver training (depending on context and availability of funding)

- access to a web-based fleet management system.

Not included in VRP rental rate

- telecom equipment ordered by the operation

- additional equipment: snow chains, spare part kits, roof rack

- all charges linked to the delivery of a vehicle: shipping, in-county transport, customs duties, taxes for import, port and warehouse charges, etc

- all in-country charges: registration, vehicle insurance, local third-party liability insurance, etc

- all operating costs, including fuel, maintenance and repairs

- all charges linked to the return of the vehicle to a VRP stock centre or secondary destination (as requested by global fleet base): customs duties and taxes for re-export, cost to deregister the vehicle in-country, transportation, port and warehouse charges, etc.

- any costs for additional repairs resulting from the loss of or improper documentation relating to a vehicle’s maintenance history

- any costs for additional repairs at the end of the rental period, for damage considered beyond the normal wear and tear.

Using another National Society’s vehicles

Most National Societies (NS) use a mileage rate that they charge for the use of their vehicles by Partner National Societies (PNS). Alternatively, they may charge a monthly fee or let PNS use their vehicles and only charge them the cost of fuel.

Mileage rates and what they include often differ, and it is recommended to clarify what is covered (fuel, driver costs, maintenance, etc), and how the amounts to be recharged will be calculated.

Choosing the best vehicle ownership solution

British Red Cross owned vehicles

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Vehicles belong to British Red Cross.

- At the end of a project, these can be disposed and realise residual value.

- British Red Cross is free to donate these vehicles to any partner of choice after the end of a project or five years.

Risks for British Red Cross

- British Red Cross must source the vehicles and ship to operation where required.

- Some governments force international organisations to donate vehicles to their governments at the end of a project.

- Vehicle must be managed as an asset (including depreciation).

- British Red Cross must spend large sum to buy the vehicles outright.

- If mission is cancelled or discontinued at short notice, British Red Cross is stuck with these vehicles.

- It is difficult to increase/reduce fleet size at short notice, but surge option plans can be built in.

- Donor constraints on expenditure.

IFRC’s vehicle rental programme

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Monthly vehicles rental cost is known, so easy for budgeting purposes.

- Access to standard vehicles.

- There is good scalability of fleet.

- Vehicles comprehensively insured at global level by IFRC.

- IFRC will replace vehicles after 150,000km or five years, whichever comes first (in-country costs associated to vehicle change will need to be covered by the requesting , but all other costs covered by ).

- IFRC will provide fleet management support, including cost tracking and driver training.

- There is no cost of disposal.

Risks for British Red Cross

- Solution includes shipping the vehicle into operation area and shipping out after the end of the lease, which can delay the availability of the vehicle to the operation.

- After five years, vehicle still belongs to IFRC and British Red Cross cannot donate it to partners.

- It can be expensive in the short term, considering shipping costs into and out of operational area.

- IFRC will charge a programme support recovery fee.

Local vehicle rental

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Locally available and no importation costs or delays.

- It is easy to scale up or down.

- It is easy to arrange at short notice.

- It supports the local market.

- Budgeting is easier when rates (including maintenance and service) are fixed.

- There is no need to have own maintenance facilities or resources.

Risks for British Red Cross

- Rental rates can be very high.

- There may be a maximum mileage under the rental scheme.

- Locally available vehicles may not be of a good standard.

- Local maintenance practices may not be safe.

- The right vehicles are not always locally available.

- Renting vehicles from questionable business people could result in bad reputation by association. Consult international sanctions lists before entering a lease agreement.

Using other National Societies’ vehicles

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Vehicles are readily available and easy to scale down.

- It gives support to movement partner.

Risks for British Red Cross

- It is not always easy to scale up (they might not have enough vehicles).

- It is only possible with small requirements.

- Vehicles are not always of a good standard.

- British Red Cross can only use what the partner has excess of or does not require.

Read the next section on Resourcing for fleet management here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Fleet

Definitions

Learn more in the Definition of fleet section.

Building a fleet strategy

Learn more in the Defining fleet needs and Resourcing for fleet management sections.

Fleet sourcing: procurement and rental

Learn more in the Resourcing for fleet management section.

Fleet management

Learn more in the Vehicle usage and Managing fleet sections.

Fleet disposal

Learn more in the Fleet disposal options section.

Fleet documentation

Learn more in the Fleet audit trail section.

British Red Cross driving procedure

Learn more in the British Red Cross domestic fleet management systems and procedures section.

Download the whole Fleet chapter here.

Some donors, destination countries and governmental bodies require that goods are inspected when they arrive in country, to ensure they have not been damaged in transit and that the goods entering the country match the customs declaration (shipping documents) and respect the quality standards imposed by the country.

There is a limited number of companies that provide inspection services and their rates are usually based on their local branches’ fees, transport fees and laboratories’ fees. These rates will often lack transparency and are hard to pass on to donors if they have not been pre-agreed in an approved budget, so it is important to include an assessment of the needs for inspection services in the review of the project design phase (see International Quality Methodology (IQM) guidance documents for more details on this). SGS and Intertek are the two major inspection service providers in the world.

Wherever possible, ensure that the inspection process is managed by either the selling or the shipping party, as they will manage the relationship with the service provider more effectively.

Inspection controls can also be required at departure. They are usually best managed by the selling party, but this is not always permitted, and donors or governments may have appointed independent inspection agents to sample and test some shipments.

Read the next section on Planning, tracking and reporting on transport here.

Download full section here.

Procuring for transport

Organisations often do not have the means to fulfil transportation requirements internally. The appropriate fleet might not be available, or the right skills may be difficult to source; knowledge of the local market, infrastructure or legal framework may also be scarce.

When transport requirements cannot be fulfilled with internal resources, they must be outsourced to professional companies. Transport service providers must be selected carefully, as they will be handling goods and materials owned by the organisation and, in most cases, distributing them to beneficiaries.

Be aware that in the context of crises or an increased humanitarian response, it might be difficult to source those services as competition for them increases. In those situations, it is recommended that organisations share the available resources by liaising with other Red Cross Movement partners to identify efficiency gains through sharing fleet.

Where operational, the Logistics Cluster can organise shared transport services on standard routes. Local/national authority coordination resources (such as the National Disaster Management Office) may also support resource-sharing where the Logistics Cluster is not mobilised.

Sourcing transport services

The supply chain strategy for a programme may include the procurement of vehicles to transport people and goods. Where this is not included, renting/leasing vehicles (and possibly drivers) will need to be considered.

In some contexts, a single service provider will be able to provide transport services for both goods and people, but in most cases two separate suppliers will have to be identified.

Selecting a transport service provider for the movement of people

For selecting a transport service provider for the movement of people, refer to the Procuring fleet: process, selection criteria, delivery section of the Fleet chapter.

Selecting a transport service provider for the movement of goods

Below are a set of criteria that should be considered when sourcing a transporter. Note that these criteria are particularly relevant in long-term agreements and less so where transport services are sourced ad hoc.

- Owns or has access to a bonded warehouse to protect and control shipments in transit.

- Is licensed by the government to conduct customs clearance formalities and is up to date on changes in customs regulations.

- Offers a variety of services (freight booking, re-packaging, clearance, etc.).

- Has influence in the transport market, with port authorities, etc..

- Has an established reputation; has been in business for a number of years.

- Has a proven record of reliability, accuracy, timeliness, as verified by customer references.

- Has experience working with humanitarian actors.

- Owns fleet for inland transport and has access to specialised vehicles when needed.

- Has trained, competent, experienced and trustworthy staff.

Transport needs assessment

Before going to market to source transport providers, it is recommended that you complete a needs assessment and to capture its result in the issued sourcing document (RFQ, tender or EOI – see the Sourcing for procurement section for details on the sourcing process). The needs assessment should detail the below requirements at minimum.

- nature of the goods to be moved

- any specific constraints relating to the type of goods

- expected delivery timeline and frequency

- expected delivery points

- cost coverage (fuel, maintenance, insurance, tolls, loading, driver per diem, etc.)

- compliance with Red Cross code of conduct

- cross-border requirements if applicable

- weight and volume of goods to be transported.

Assessing the local transport services’ market may include pre-qualification of service providers available. This will involve identifying as many potential suppliers as possible and asking them a series of questions to assess their suitability.

Depending on the expected volume of expenditure, and following applicable procurement procedures, an RFQ or RFP can then be sent to these pre-qualified suppliers with the details of the services needed.

Sourcing process

The sourcing document should clearly reflect the findings of the needs assessments and set out the selection criteria. For details on the recommended procurement processes, refer to the Procurement processes in the British Red Cross and Sourcing for procurement sections of the Manual.

Prior to the award of the contract, it is recommended to have face-to-face interviews with the successful supplier to review contractual terms such as:

- expected turnaround times (and any seasonal variations on this)

- cost per trip per load (if the routes are unlikely to change)

- contact focal points

- validity of quoted rates

- contract length

- payment terms

- penalties when agreed service standard is not reached.

Remember to select the right costing options for your needs – you can request a quotation per day, per type of vehicle, per ton or per route.

A template transport contract is available here and at the end of the section.

| Contract type | Details | Use when |

|---|---|---|

| Task-specific (one-off) | Quote based on set quantities, set schedule, set origin, set destination, limited timeframe | Needs are specific and limited in time and quantity There is a pre-defined budget for the service There is a single expression of needs (one requisition) |

| Open contract | Quote per vehicle type and per period (day, week, month) or per route | Long term projects with regular routes and needs Transport services market is stable and services can be scaled up and down There are multiple requestors for transport services |

Available to download here.

Transport service provider evaluation and performance management

It is important to agree evaluation criteria for the service provider’s performance monitoring, so the service provider has an opportunity to improve their performance across the duration of the contract.

It is good practice to hold quarterly meetings with regular service providers to review performance against set key performance indicators (KPIs). This requires careful recording of performance data on all shipments carried out by the service provider, a task that must be appropriately resourced internally.

Appropriate points of analysis and performance to evaluate transport service providers may include the below data points.

- total volume transported (weight, volume, value)

- per cent of shipments received on time in full (OTIF) per contractual schedules and damage definition

- number of claims raised, total value of claimed damages

- per cent of properly documented services (returned signed waybills etc)

- variations from contractual rates

- total spend to date against total value of contract (“burn-rate”)

- options to extend the value or duration of the contract

- actual availability of resources against contractually agreed availability (drivers, loaders, vehicles…).

Transport service providers can also be contracted for single operations, whether they involve a single transportation or multiple pick-ups and deliveries. In that case, the right selection and procurement processes must be followed for the estimated cost of the operation and the contract terms will slightly differ, as the costs and services will be pre-agreed. Penalties should still be agreed, but where the services required are to be completed over a short period of time (less than three months), the supplier performance review is limited.

Sourcing clearing agents

Clearing agents

Clearing agents can offer similar services to freight forwarders – they occasionally offer transport services from the point of entry into the destination country to the final delivery place. However, their “core” service offer is the clearance of goods through the destination country’s customs.

Clearing agents can be a valuable source of information in helping to anticipate issues that may arise during the customs clearance process.

In some countries, the government will impose a mandatory clearing agent; some shippers (senders/sellers) will offer services from a partner clearing agent in their quote, and some consignees (receivers) may recommend a partner clearing agent. Where clearing agents are recommended, it is usually good practice to use them rather than sourcing alternative agents. Where there are no suggested clearing agents, these must be sourced through a procurement process.

Selecting a clearing agent

The process and selection criteria are like those used when selecting a freight forwarder, with some more specific criteria to consider (that should have been identified in the transport needs assessment).

Below are some key requirements that should be included in the RFQ/EOI/tender document.

- is licensed by the government

- can handle road, air, sea shipments

- can provide details of procedures to follow for all types of goods ahead of shipment

- has offices located close to the entry points (port, airport, etc.)

- has access to a network of (bonded) warehouse

- can guarantee delivery to final destination

- has experience working with the humanitarian sector

- works with a network of licensed agents

- can share details of customers to provide references

- can share details of their client portfolio – contracting a clearing agent who will prioritise more important customers could be a critical risk to the delivery of supplies.

Sourcing a clearing agent

The sourcing document should also specify the criteria that will be used to evaluate the offer, some of which should be based on the list in the Selecting a clearing agent section above. As a result of responses to the above requirements, you may want to contract multiple clearing agents (one for air shipments and one for sea shipments, for example). You can also choose not to have contracts in place but a list of pre-qualified, pre-vetted agents, who would provide you with quotes on a shipment-by-shipment basis.

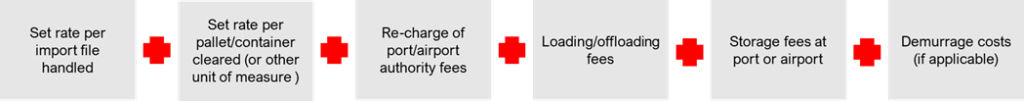

Note that the clearing agent’s fees structure is typically quite complex, and includes the following:

Remember to ask your clearing agent to provide the breakdown of the costs they forward to you in their invoices. Demurrage costs in particular should be clearly explained ahead of the clearing process.

Clearing agent evaluation and performance management

It is important to agree evaluation criteria for the clearing agent’s performance monitoring in the contract (or as an annex to the contract if they are linked to penalty fees). That way, the clearing agent will have a clear understanding of their client’s expectations and they are given an opportunity to improve their performance through the duration of the contract.

It is good practice to hold quarterly meetings, with regular reviews of performance against the KPIs that have been set. This requires a careful recording of performance data on all shipments carried out by the service provider, a task that must be appropriately resourced internally.

Appropriate key performance indicators to review clearing agents’ performance may include:

- average time taken to clear goods through customs (per mode of shipment), compared to contractually agreed time

- invoiced costs compared to quoted costs

- number of claims raised for losses or damages in transport and total value of claimed damage

- a review of cases where the process that was initially suggested had to be revised due to a lack of understanding of the specifics of the cargo

- demurrage costs incurred.

Note: demurrage costs are charged by port or airport authorities when shipments stay on their premises beyond an agreed number of days. They can add up very quickly as they are usually formulated per container or per pallet and incurred daily. They can be avoided through pre-defined agreements or preferential arrangements between clearing agents and port or airport authorities. They should be paid by the party responsible for the delay, but they are extremely difficult to waive once incurred.

Working with clearing agents

To process a shipment through customs, the sender or receiver of the goods (depending on the incoterm in place) will generally have to submit the shipping documents to the clearing agent in advance of the arrival of the cargo.

The type of documents understood by “shipping documents” will vary from shipment to shipment but will almost always include:

| Document | Function | Provided by |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial or pro-forma invoice | Declare total value of goods to be cleared | Seller |

| Packing list | Provide physical details of consignment and detailed contents | Shipper if sold EXW Seller if sold on any other incoterm |

| Donation or gift certificate (if relevant) | Declare 0-value of goods to be cleared and allocate ownership of goods to consignee | Shipper |

| Certificate of origin | Declare origin of goods | Manufacturer/seller |

| Certificate of analysis | Provide quality assurance certificate | Manufacturer/seller |

| Good Manufacturing Practices certificate (GMP) | Provide quality assurance certificate | Manufacturer/seller |

| Draft and final shipping title | Provide quality assurance certificate | Shipper if sold EXW Seller if sold on any other incoterm |

Available to download here.

Note: a gift certificate template is available in the resources for this section.

Read the next section on Sourcing inspection services here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Mapping a warehouse

Once the storage space has been identified, it will need to be optimised for your planned needs. Areas to be included in the storage map are:

Bulk storage area

- This is where the majority of items will be stored – it can be densely organised.

- Items in most regular demand should be closest to the goods receipt/dispatch/picking areas.

Goods receipt area

- Estimate its dimensions per the expected incoming volumes: if you expect to receive items in 20-ton truckloads, make sure your reception area is large enough to store the corresponding volume.

Goods dispatch area

- Estimate its dimensions per the expected outbound volumes: if you expect to dispatch items in 20-ton truckloads, make sure your dispatch area is large enough to store the corresponding volume.

Picking area

- Depends on the dispensing units: if items will be dispatched in a smaller packaging unit than they come in, you will need a picking area (bulk construction items such as nails, bolts or medicine, as you will dispense packs or bottles in smaller quantities than the base carton quantity).

Truck docking area

- For trucks to station and manoeuvre and offload. Include level docking platform if possible.

Office space

- Ensure office space can be isolated from noise and vehicle movements and is ventilated.

- A safe path to the office space must be kept clear at all times.

Packing materials storage area

- Use to store carton boxes, pallets, wrapping and strapping materials.

Cold chain area

- For items which require specific temperature conditions.

- Move close to power supply source and ventilation.

Quarantine area

- For expired, damaged items or items pending inspection or test results.

- Must be lockable.

Sanitary facilities and breakout area

- Ensure respect for cultural norms.

Emergency exits and fire fighting equipment

- Must be signalled clearly.

Security shed/corner

- For security personnel to use during shifts and to store their work equipment. Should be located near the main entrance to the warehouse compound.

A table detailing the different areas is available to download here.

Each of the areas should be clearly separated from one another and space between stacks, racks, shelves or pallets must be included to allow for passage and cleaning.

Depending on how the goods will be handled (manually or with specialised equipment), the space between storage blocks will be different. For human handling, 1.2m is usually enough. Where specialised equipment (forklift, sack truck or hand pallet truck) is used, the manufacturer will be able to confirm the required turning circle.

Each storage unit must be at least 50cm away from the main wall of the warehouse.

Standard layouts include:

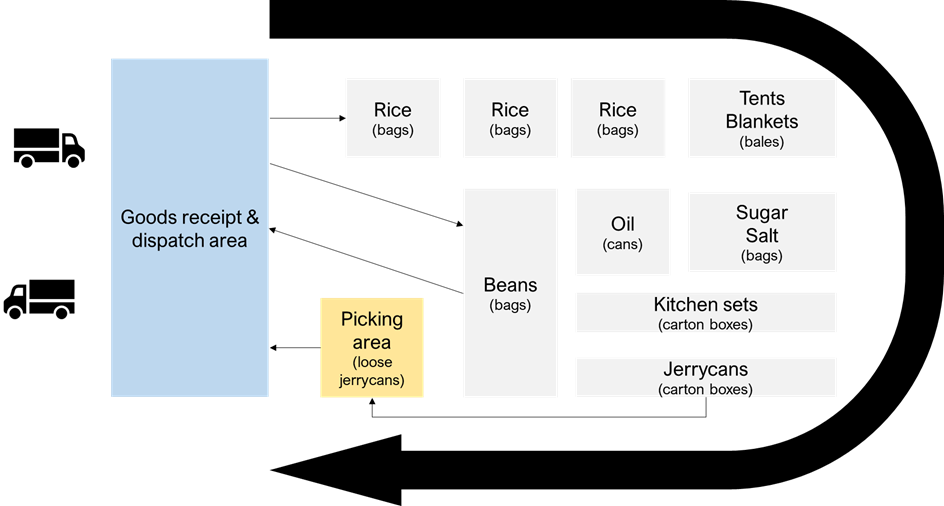

U-flow

Available to download here.

U-flow is used when the receiving and loading areas are next to each other on the same side of the building. It provides the following features:

- Because the receipt and dispatch areas are side by side, the space can be used flexibly, particularly if these activities are scheduled to take place at different times in the working day. This can save space.

- Personnel and equipment can be used in a flexible way, reducing the overall requirement for resources.

- Because the main access to the building is in one place, access and security are easier to manage.

- The building may be extended on three sides where required and where the site allows.

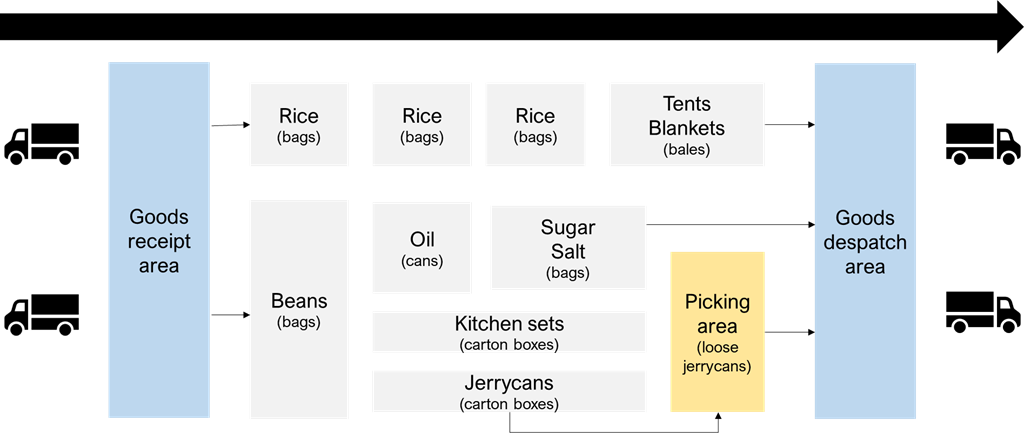

Through-flow

Available to download here.

Through-flow is used when the receiving and dispatch areas are at opposite ends of the building. It tends to be used under the following conditions:

- Where vehicles and equipment used in receipt and dispatch are of different types.

- Where the flow of vehicles around the site will be facilitated (there may be separate gates at opposite ends of the compound for example).

The warehouse manager should ensure that all areas of the warehouse are physically identified, and a map of the warehouse must be available and posted on its walls.

Equipping a warehouse

Depending on the type of goods to be stored, the activities that will take place in the warehouse and the equipment available, the warehouse will have to be fitted with office equipment, specific storage equipment, additional safe storage space and/or partitioning.

In certain cases where the warehousing activities are expected to be critical to the operation and include large volumes of items, it may be relevant to invest in handling equipment.

In all cases, the storage facility will have to be equipped with a fire prevention system.

Storage options

A stack is a pile of the same item on a warehouse shelf.

Goods must be stacked separately and sorted by programme ownership, expiry dates or final destination, for example.

A bin card must be physically attached to each stack or grouping with the same , batch number and expiry date.

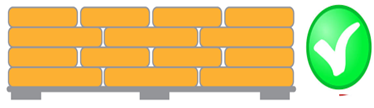

Wherever possible, stacks should be placed on pallets and not directly on the floor. Where possible, they should be wrapped in plastic sheeting or tarpaulins.

Where supplies of pallets are limited, note that bagged foods are more vulnerable to humidity than canned or bottled products, so food items should be palletised in priority.

Where pallets are not available at all, items can be temporarily stacked on plastic sheeting laid on the ground.

The distance from stacks to walls and between the stacks must allow a person (or a forklift if using) to pass and be at least 50cm.

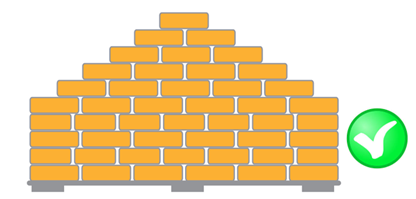

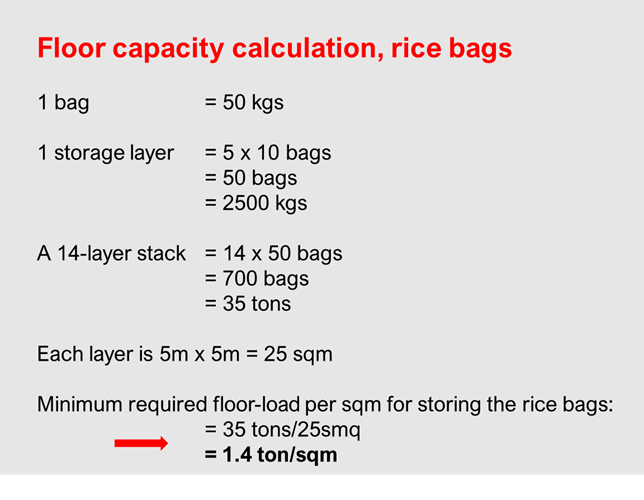

The recommended size of a stack is 5 x 5 metres and a maximum 2.5 metres high with bags stacked by 5 x 10 = 50 in each layer x 14–15 layers (= ~ 700 bags).

The stack height will be affected by the type of packaging; boxes and jute bags stack higher than woven polypropylene bags, which tend to slide. When stacking cartons, ensure that lower packages in the stack are neither crushed nor torn. Commodities packaged in tins and plastic bottles, have lower restrictions in terms of maximum stacking heights.

In addition to height restrictions, oil packages frequently indicate a recommended maximum number of rows for stacking. Check the instructions on packaging, where they exist, or consult the suppliers for information.

Where stacks are tall, it is useful to tie a rope around the top layer to stabilise them.

Bags that need to be stacked higher than 2.5m should be stacked up to 2.5m as shown here, with the additional layers stacked in a pyramid to avoid slippage. Plastic sheeting can be added between layers to prevent slippage.

Volumetric storage

Create a one-cubic metre container to measure sand, gravel or a quantity of construction materials in bulk. This works well for timbers, poles, bamboos and items stored in “bundles” of 100 pieces for example.

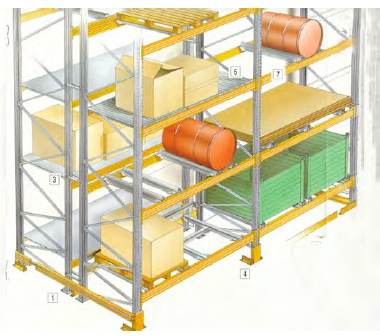

Pallet racks

Simple pallet racks usually have two or three tiers. Two tiers of pallet-racking require a clear total height of about 3 metres and three tiers require a clear total height of about 4.5 metres. It is possible to have more tiers, but sophisticated mechanical handling equipment is then required.

The benefits of shelving and pallet-racking can be combined. The bottom tier of racking may be used to store the working stock if arranged at a convenient height for manual order picking. Alternatively, a special picking shelf can be placed immediately above the bottom tier of pallets. In both cases, the upper tiers can be used to store safety stock or bulk stock. Caution: check the racks’ load-carrying capacity with their owner/manufacturer or an independent engineer before using them and check every rack regularly for signs of damage.

Keep space between the racks and the walls, ensure that the racks are stable and, where possible, fixed together and to the wall and/or to the floor.

Large racks

Large racks are useful when storing large inventories of a variety of types, and where the dimensions of pallets are not the standard dimensions of packaging. The racks pictured here have the advantage of adjustable racking height.

Leave space between the racks and the walls.

Ensure that the racks are stable and where possible, fixed together, to the walls and/or to the floor.

Shelves

Use shelves where there are a lot of small items and/or when there are items that need repacking or picking (medical supplies, kits, etc). Storage on shelves does not require mechanical handling. In tropical countries where termites attack wood, metal structures are preferred. Shelves can be taken apart and adjusted to suit the goods to be stored.

Keep space between shelves and walls to improve ventilation.

Choosing the best storage options

Bulk items (loose)

- volumetric storage

- 1,000 kg = Variable volume

- volume defined at item level, as item density varies

- 1,522 kg of gravel = 1cbm

- 1,922 kg of sand = 1cbm.

Food in bags (grains. flour, sugar, salt)

- stacked on pallets, with chicken wire between pallet and supplies

- 1,000 kg = 2cbm.

Food in cans or bottles

- stacked on pallets

- 1,000 kg = 1.5 cbm

- ask manufacturer for maximum stacking layers.

NFIs in boxes

- stacks

- adjustable racking

- check stackable height where items are fragile.

NFIs in bags or bales

- stacks (fenced)

- adjustable racking

- 1,000 kg = 8-10cbm

- stacks if stable

- adjustable racking preferred for bales.

Construction materials

- bundles of xx units

- 1,000 kg = Variable volume

- keep stacks fenced with timbers or wiring.

Medical supplies (drugs)

- large racks for main storage

- shelves for picking units.

Medical equipment

- Pallet racks or large racks.

A table detailing the best storage options is available to download here.

In addition to the above, note that to store medical and/or food items you will likely need:

- cold chain equipment: passive (ice packs or other isotherm systems) and active (power-generated)

- a locked storage space for controlled substances

- a quarantine area equipped with shelves/racking.

See the storage of food and medical supplies sections in Managing a warehouse.

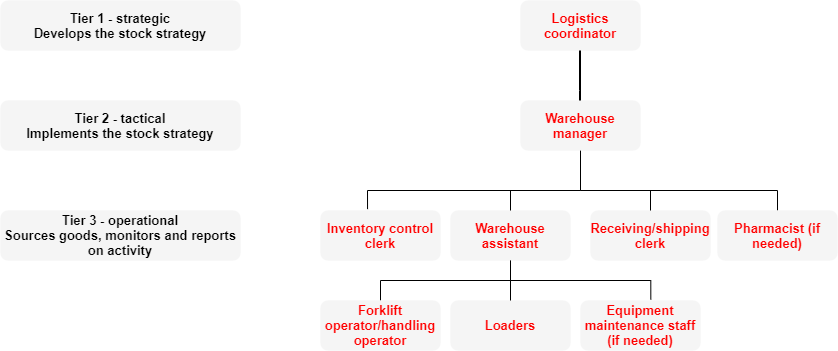

Manning your warehouse

Based on the process mapping exercise (part of the stock strategy definition – see the How? section of Stock strategy definition in Building a stock strategy), adequate resourcing will be required for the operation of the warehouse.

The size of the warehouse team will depend on the size of the operation, and the allocation of tasks should be adjusted accordingly (one member of staff may cover several of the below functions). Below is a standard organisation chart including all the skills needed to operate a warehouse.

Available to download here.

Recruiting a warehouse team

Standard job descriptions are available on request from the international logistics team.

The logistics team can provide examples of written tests for recruitment on request, should you need them.

Guards and security staff and services can be either hired as staff or day labourers, outsourced as a service or included in the lease of the warehouse. Where guards are hired as staff or day labourers, the warehouse manager will have to define working patterns and shifts (rota). Ideally, these should be captured in a guards’ shift planner.

Some situations will call for a set of core permanent staff, with the arrangement for temporary staff to meet periodic increases in demand or workload. Holding a register of daily workers with contact details and specific skills, managed by the warehouse manager only, can be useful.

Host National Society (HNS) volunteers can also help in the warehouse during periods of high activity, but this must be agreed with the HNS and their procedures and practices must be observed in terms of volunteer hours, incentives and payments. Do not engage volunteers as regular staff without prior approval from and consultation with the HNS.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Hired as staff | Permanent staff with benefits Can be trained and retained | Must manage working hours and performance directly Ensure status in country allows recruitment in own NS's name |

| Hired as daily labourers | Flexible workforce Wide pool to recruit from HNS can provide volunteers | High turnover of staff |

| Outsourced | Flexible workforce Guaranteed professional service | Limited control over allocated resources - competition with other clients |

| Included in warehouse lease | Not included in head count No direct management | Limited control over allocated resources No control over ethical management standards |

Available to download here.

Managing the warehouse team

Warehouse managers are permanent staff members, staff or volunteers. They are responsible for all activities related to stock movements: the reception, storage, release, dispatch and recordkeeping for all goods.

The warehouse manager defines, schedules and coordinates the activities and resources that need to be available to deliver the mission of the warehouse. They also oversee security arrangements, control the recruitment of day labourers and manage the schedules, payment, performance and training of all warehouse personnel.

Regular team meetings should be held, organised by the warehouse manager:

| Frequency | Attending | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly | Complete warehouse team and logistics delegate | Monitor performance against set objectives and discuss updates on projects |

| Weekly | All warehouse staff | Warehouse manager to present operational objectives of the week and reflect on past week |

| Daily | Individual briefs to loaders and receiving/despatching staff | Allocate daily tasks |

Available to download here.

Where daily labourers are regularly recruited, a system must be in place to request the number required each day, record their attendance and report to finance for payment. For example, the receiving/shipping clerk should request through a daily worker request form, signed off by the warehouse manager. Attached to daily worker record sheet, the whole file should be submitted to finance for weekly payment at an agreed time. As far as possible, day labourers should only be hired as security guards, cleaners and loaders.

Read the next section on Managing a warehouse here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates

Download the full section here.

Setup options

Central, regional and distribution-point warehouses can be built, commercially rented or provided by the host National Society, the government or operational partners. Buildings designed for storage are preferred as central or regional warehouses.

Where no suitable facilities exist, the construction of temporary or permanent warehouses should be considered. Immediate and interim needs can be met through the use of specially designed warehouse tents (Mobile Storage Units, MSUs) or other temporary storage facilities.

Wherever possible, avoid sharing a warehouse with another agency and, especially, commercial firms. Where this is unavoidable, fence off different partners’ areas or clearly mark each partner’s stock. Additionally, when sharing a warehouse with another agency, a standard Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) should be signed to specify the detailed terms and conditions of the lease/sharing.

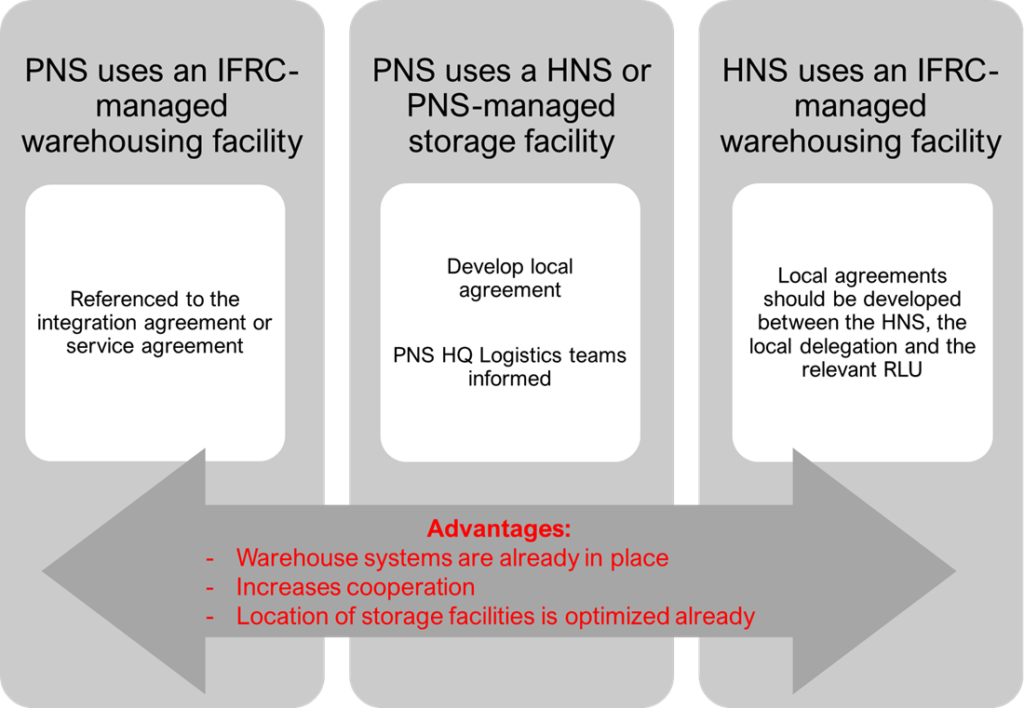

Options to share warehouse facilities within :

Available to download here.

Types of warehouse

Temporary warehouses

Tents and Mobile Storage Units

Tents can be standard tents or Rubb Hall (MSU) tents.

Tents should always be set up on flat and firm ground (preferably on a concrete slab), with ditches around their outside perimeter. If possible, add a tarpaulin or net on top of the tent, allowing space for ventilation between the roof of the tent and the additional tarpaulin. If using a tarpaulin to cover stored items, ensure that a separate tarpaulin protects the items from the ground. Make sure the tent can be securely closed with padlocks. Ideally, it should be fenced inside and out to limit access and manned with 24-hour security wherever possible.

Rubb Halls (also known as mobile storage units or MSUs) are tents that have been specially developed for emergency storage purposes. The standard model used in operations offers a maximum 600m3 of storage, and a ground surface of 240m2 for palletised storage.

Erecting a tent requires 12 people, at least one of whom must be a trained technician, and takes two days. Rubb Halls should also be lined with mesh or chicken wire to prevent theft.

Rubb Halls are usually equipped with a locking system that requires one large padlock, or two padlocks if the Rubb Hall can be opened at both ends.

- length: 24m

- width: 10m

- height: from 3m on side to 6m at ridge approx.

- materials: steel structure and UV proof PVC coated canvas cover

- logo/branding: banners that can be attached or printed directly on the canvas.

Note: Rubb Halls are available in different sizes. However, the above is as per RCRC standards and is the model deployed to most RCRC operations.

Rubb Halls can be ordered by logistics through the or the or directly from the supplier. The British Red Cross holds Rubb Hall tents in the IFRC in Panama, Kuala Lumpur and Dubai. Rubb Halls are only to be released for extremely urgent and rapidly onset operations, with a strong business case and approval of the relevant international logistics coordinator.

Good reasons to deploy a Rubb Hall include:

- Where there is extensive damage to buildings.

- Temporary increase of stock in emergency situations (where warehousing space is already available but insufficient to absorb increased stock).

- Pre-positioning of stock in remote locations where there is no infrastructure.

- Legal response where humanitarian agencies are not allowed to build permanent structures.

- A high likelihood that the location of the operation will change in the duration of the response.

Re-purposed containers/wagons or barges

Where no firm ground can be found or where tents cannot provide security for stock, it is possible to use shipping containers as temporary storage. If a container is used for long-term storage, it needs to be repurposed to create optimal conditions for its maintenance and for the items stored.

Detailed instructions on how to re-purpose containers, wagons or barges can be found here.

Permanent warehouse

In emergency setups, warehousing facilities will usually be rented as opposed to purchased.

Find a suitable warehouse

Characteristics of a good warehouse:

- solid building with a firm, flat floor

- dry and well ventilated

- gives protection against animals, insects and birds.

- gives protection against humidity, extreme temperature fluctuations and local weather conditions

- easy access for trucks

- easy loading and unloading

- secure against theft (locked, gated, etc.)

- in an appropriate site – low disaster vulnerability, above flood level, away from salt spray…).

Also consider:

- size of the warehouse

- 24/7 accessibility

- Red Cross visibility

- ownership of the warehouse or the land it is on

- avoid sharing with other agencies. If this is impossible, clearly mark your area.

Agree lease conditions

- cost and payment schedule

- period of lease agreement

- period of notice for terminating or extending the lease

- include confirmation of property insurance, covering third party, fire, water damage and any damage to the structure of the building

- details of security arrangement: who will provide security services and in what pattern (number of guards, rotation times, validation of guards, etc)

- an inventory of any equipment, fixtures and fittings included with the building and a detailed description of their condition and maintenance requirements

- confirmation of sole tenancy or, where relevant, details of other tenants

- For warehousing facility – the memorandum of understanding with sharing tenants should be annexed to the lease contract

- information about the ground or floor strength

- weight capacity of any equipment included in the lease (forklift, racks shelves, etc).

- access by the landlord to the warehouse specified in the lease. The landlord should preferably notify the leasing party before accessing the warehouse.

To uphold the ’s neutrality principle, the identity of the owner of the premises (might be different from the leaser) must be known. Where the owner is linked to the military, religious authorities or government, this should be reported to headquarters for risk analysis.

Also review any previous usages of the warehouse to identify risks, such as if it was previously used to store dangerous or toxic material, weapons, etc.

A template Warehouse rental contract template is available to download here and at the end of this section.

Read the next section on Setting up a warehouse here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates

Download the full section here.

Assessing the warehouse requirement (number, location and operation)

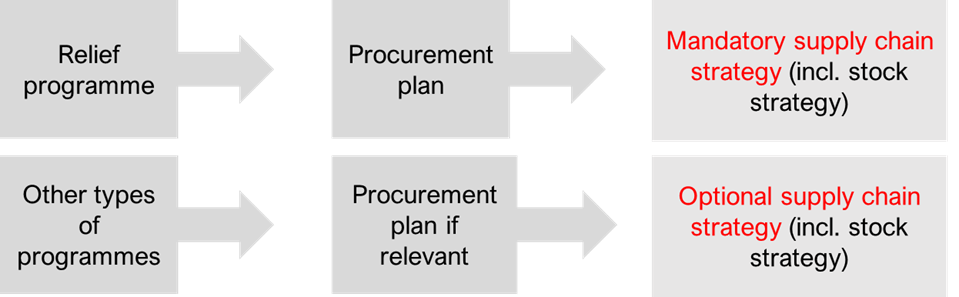

During the design phase of a programme, a stock strategy should be developed, including the potential requirements for warehousing. This should fit into the wider supply chain strategy for the programme (see supply chain strategy template and guidelines).

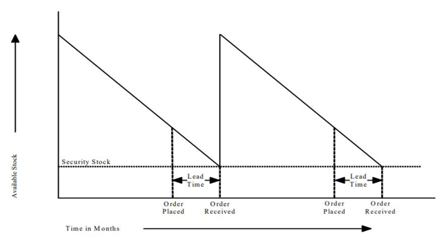

Warehouses are needed when the time required to purchase and mobilise relief items is expected to be lengthy or when responding to a protracted crisis where the risk of disruption to the supply chain is high.

A network of warehouses may also be required to ensure the rapid and efficient delivery of relief supplies. Since most British Red Cross programmes are short-term (a maximum of several years) the need for a new permanent warehouse is rarely justified, although it can be considered as a long-term solution for an supporting future programmes.

Stock strategies must be in line with organisational strategies because holding stock with a projected high value is a risk to the organisation. Other supply chain options, such as the delivery of goods taking place closer to the required time, are sometimes preferable.

Programmes should not be built around the stock strategy (What do we have?) but a stock strategy around the programme (What do we need?).

Available to download here.

Quantity and location of warehouse(s)

- type of items to be stored

- scale of operation and required stock levels

- geographic and seasonal conditions

- distances to programme site(s) and supply entry points

- infrastructure available

- availability of transport services

- lack of other storage options (vendor-managed inventory, 3rd party warehousing etc.).

-> Number and location of warehouses required for an operation

Stock strategy definition

View the stock strategy definition diagram here.

During the planning phase, the programme team should provide a range of information to enable logistics to develop a stock strategy.

What?

Storage requirements vary depending on type of items.

Medical supplies and drug shipments can contain small and high value items, many of which have a limited shelf-life.

A secure area is required, and close attention must be paid to expiry dates.

Antibiotics and vaccines require temperature-controlled cold storage arrangements, with sufficient capacity and a reliable power source, with a back-up option.

Combustible items such as alcohol and ether must be stored separately, preferably in a cool, secure shed in the compound and outside the main warehouse.

Non Food Items (NFIs) can usually be stored in bulk with no specific storage or handling limitations.

Dangerous goods such as fuels, compressed gases, insecticides and other flammable, toxic or corrosive substances, are hazardous.

International regulations require specific markings to identify their dangers.

Consider the volumes to be stored: the quantity to be stored and the frequency and size of deliveries and dispatches will influence the stock strategy definition.

Consider whether the stock strategy will involve holding and handling kits in stock. If so, how much kitting activity is expected to take place in the warehouse? Kits are often used in emergencies, when the aim is to provide large quantities of a standard set of items to large numbers of people.

The IFRC standard product catalogue (SPC) includes a wide variety of kits, normally provided as full kits by long-term suppliers sourced by the .

Detailed information on handling hazardous substances can be found here.

Detailed information on managing kits can be found here.

Where?

Where is the programme being implemented and where are the goods required?

Think about: