Note: In the following sections, vehicles can be cars, trucks, planes, or ships. Where variations from the process occur, they are detailed at each step.

When planning inbound movements of freight (i.e. receiving a consignment):

Preparing for reception

The sender must always inform the consignee ahead of shipping goods, sharing as much information as possible on the shipment before the vehicles leave for delivery.

Information to share ahead of shipping:

- expected arrival date and time

- goods transported: a draft packing list or reference to orders (requisition), estimated weights and volumes

- vehicle details: registration, driver/pilot details and route. For sea shipments, this will be vessel route and shipping line

- special requirements: cold chain, dangerous goods, bulky equipment, etc.

- details of vehicles: schedule, number of trips and prioritisation.

The receiver should confirm their capacity to handle the inbound shipment and make necessary arrangements.

Arrange your reception area to ensure the full consignment can be temporarily stored before being moved into the bulk storage area – if necessary, make temporary adjustments to the warehouse layout to accommodate the incoming consignment.

Communicate temporary changes to the layout to the warehouse team.

To prepare for reception:

- plan for space to offload

- plan for documentation to track offloading process – ensure a detailed packing list is available

- plan for available manpower to offload

- plan for cold chain capacity if needed

- re-schedule planned orders with the warehouse team and end users

- prepare labels for storage

- rent or procure handling equipment if necessary

- prioritise processing order with end users.

Information to share after shipping:

- container seal number where relevant

- expected ETA

- copy of final transport document (waybill, bill of lading, air waybill, CMR where relevant)

- exact contents of consignment: final packing list, weights & dimensions, specific handling requirements and markings

- contact details of driver/pilot and rental company (if relevant).

The captain of a vessel can usually not be contacted directly, but vessels can be tracked by a bill of lading.

Note: where the shipper of the goods is the supplier of the same goods, the same details must be obtained from them.

| Sharing shipment details | Provided by | |

|---|---|---|

| Responsible | Shipper | Receiver |

| Accountable | Receiver | Receiver |

| Consulted | Receiver/requestor | Requestor |

| Informed | Requestor | Shipper |

At the time of reception

| When to count containers | When to count pallets | When to count boxes | When to count boxes' contents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | N/A | At airport if palletised | At airport if unpalletised At delivery place if palletised | At delivery place |

| Sea | At port | At port if possible At delivery place otherwise | At port if possible and unpalletised At delivery place if palletised | At delivery place |

| Road | At delivery place if relevant | At delivery place if relevant | At delivery place | At delivery place |

| Rail | At delivery place if relevant | At delivery place if relevant | At delivery place if relevant | At delivery place |

Available to download here.

Note: counting the contents of sea freight containers (pallets, boxes, loose goods, etc) can often not be done at the port and has to be done either at the final delivery place or at the freight forwarders/clearing agent’s premises.

Road consignments will usually be delivered straight to the delivery point. At the time of offloading, make sure every unit (pallet or box) is accounted for, and store them separately until the entire content of the boxes has been reviewed against the shipping documents accompanying the truck. Where a transhipment is needed, all pallets and boxes must be accounted for during the transhipment.

At time of reception:

- Check that all documents are attached to the consignment: commercial invoice, gift certificate, packing list, waybill, bill of lading, air waybill or CMR sheet (where applicable) and any customs clearance certificate (including tax waiver documents where applicable).

- Check that container seals are in good condition.

- Check the condition of each box/pallet as it is offloaded and check for labels.

- Confirm number of boxes matches the consignment documentation in each vehicle/container.

- Check and inspect the contents of each box to confirm exact quantities received against the packing list attached to the consignment.

Record any discrepancy and reconcile only once all boxes have been inspected (sometimes all ordered goods are in the consignment, but the packing lists are not accurately broken down per packaging unit). - If receiving a cold chain consignment, read the temperature-monitoring devices attached to the consignment, to confirm cold chain has been maintained throughout the transport process.

Offloading trucks

If available, use loading docks or platforms. Otherwise, position the truck on level, solid ground, as close as you can to where the goods must go to.

Allow enough space for movement around the truck, especially if you are using a forklift truck or hand pallet truck.

If you have inbound trucks and outbound trucks available simultaneously, consider whether it is worth trans-shipping directly from one truck to the other (as long as you can control the process and ensure accurate counting is done).

If handling equipment is not available, do not throw unidentified goods from a truck but hand them down carefully.

If goods must be manually handled because there is no handling equipment, use a chain of people (with one person in charge). The chain must have enough people for each person not to have to ‘walk’ more than one step. The people should be placed facing alternately along the chain to avoid unnecessary ‘twisting’.

View an example diagram of correct offloading of trucks here.

Avoid handling goods more times than you must by only putting them down where they have to go, in the stack they have to go in (see the Storage options section of Setting up a warehouse for more information on stacking). If the person you are handing the goods to is not ready, call the chain to stop.

Always maintain height if you can. Do not put goods on the floor if they must be lifted up again.

Make sure someone who is not handling the goods is counting as the goods are moved. That person should keep a tally (marking off per layer removed or built, for example), in case they get interrupted and cannot remember where they had counted to.

A check count should be done when each stack is created.

When all goods are offloaded, cross-check offloaded quantities against shipping documents and make note of any discrepancy.

Remember to take breaks when needed during offloading and make sure drinking water is readily available.

Documenting the reception

For details on how to receive goods in a warehouse, see the Receiving stock, Document the reception, Receiving stock for the British Red Cross (in UK or at Regional Logistics Units) and Releasing stock sections of the Warehousing chapter.

After reception of the goods

Record all received quantities on the appropriate stock cards and bin cards, referring to the GRN/ as appropriate.

Transfer the goods from the reception area to the main storage area as soon as possible.

In case of any claims, follow up on resolution options with the sender/transporter, agreeing on corrective measures to be put in place for future shipments where relevant.

Log the shipment in a shipment tracker, with complete details of the consignment – this will be used in the activity reporting process.

Inform the requestor and sender of completed delivery: share a copy of the GRN. Detail any measures being taken to address claims and raise (where applicable).

For more details on the reception of international cargo, refer to the Warehousing chapter.

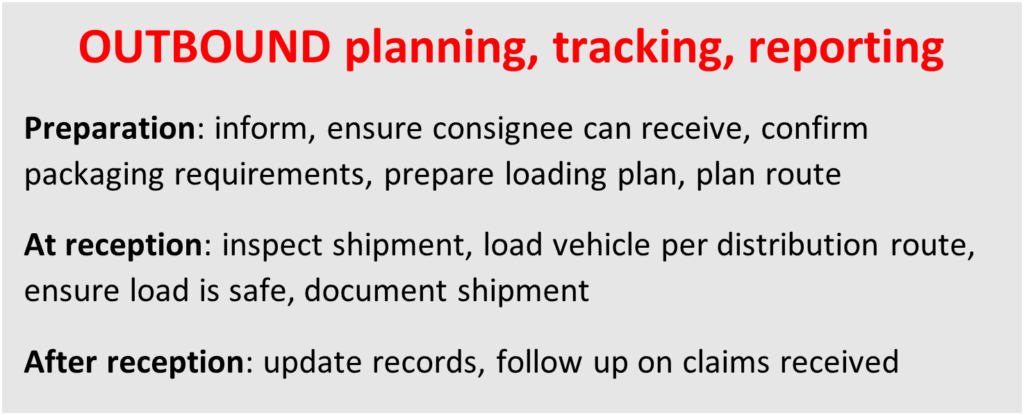

Preparing outbound shipments

When planning outbound movements of freight (i.e. shipping a consignment):

The sender must always inform consignee ahead of shipping goods, sharing as much information as possible on the shipment before the vehicles leave for delivery.

Information to share ahead of shipping:

- expected arrival date and time

- special requirements: cold chain, dangerous goods, bulky equipment, etc.

- goods transported: a draft packing list or reference to orders (requisition), estimated weights and volumes

- details of vehicles: schedule, number of trips and prioritisation

- vehicle details: registration, driver/pilot details and route. For sea shipments, this will be vessel route and shipping line.

Move the goods to be shipped to a designated dispatch area. The dispatch area can be temporarily modified as necessary, but make sure the warehouse team is informed of any changes.

Inspect the goods to be shipped: are all packaging units in good condition? Ensure cartons/pallets are stripped of any markings that could lead to confusion.

What are the packaging/labelling requirements? Be sure to ask the transporter and the consignee about any specific requirement they may have. Shipping instructions will also be helpful to find information about such requirements.

What will be the route of the vehicle, and the shipping mode? This will impact the loading plan and must be agreed with the transporter as early as possible. When sending sea shipments, control over the loading plan will be with the shipping line.

Where temperature control is required, cold chain materials (thermometer, temperature tracking devices, cool boxes, icepacks, etc.) must be made available.

Raise a final packing list with all details of the consignment. In the Red Cross movement, the waybill is often used as a packing list however it is sometimes easier to use both documents separately (for very large consignments for example).

Use a load optimisation tool to determine best transport options (this only works for road shipments).

Place the request for the necessary vehicles well in advance (as per the terms of the service-level agreement defined in the contract, where relevant), ensuring that you receive driver/pilot details and a vehicle registration certificate before the shipping date.

Ensure the necessary manpower and loading equipment will be available for loading the vehicles.

When using shipping containers, make sure the use of the containers is optimised and suggest changes in quantities where relevant (e.g., when five per cent of the order does not fit into a single container, the consignee might be willing to postpone the delivery to save the cost of the extra container).

Based on the number of packaging units shipped, prepare a loading sheet to give to the loaders, so they can track the progress of the loading process.

Where multiple vehicles are transporting multiple items, agree in advance the load composition (i.e. whether each vehicle holds a combination of all the items or only one type of item).

Loading trucks

- If available, use loading docks or platforms. Otherwise, position the truck on level, solid ground as close as you can to where the goods have to go to or come from.

- Allow enough space for movement around the truck, especially if you are using a forklift or hand pallet truck.

- If handling equipment is not available, do not throw unidentified goods from a truck but hand them down carefully.

- When loading trucks, always stack goods starting at the front of the truck and work towards the back.

- Always place the heaviest goods on the floor of the vehicle.

- Rules about stacking also apply on a truck (see the Storage options section of Setting up a warehouse).

- If you are loading a truck for distribution, lay the goods along the length of the vehicle, so that complete sets of whatever is being delivered can be distributed off the back of the truck (unless the truck has an open top or can be easily accessed from the sides, like a ‘wing’ truck).

View an example diagram of a truck loaded for direct distribution here.

At the time of dispatching

- Hand out loading sheets to loaders and retrieve them after the vehicle is loaded.

The loading sheet should simply list all the parcels to be loaded, and one loader should monitor loading progress by ticking the parcels off as they are loaded on the truck. - Confirm the route of the vehicle.

- Raise a waybill, detailing the quantity of units (pallets, sacks, boxes) loaded, weight and volume per unit and total weight and volume of the consignment.

Alternatively, waybills can detail the total quantity, weight and volume per item included in the consignment (in particular when goods are sent unpalletized or loose). - Place seals on containers where necessary.

- Ensure load is safe (with no risk of spillage or cross-contamination, etc) and securely fastened inside the vehicle – straps can be used, or blankets can be used to secure a load on a half-empty truck, for example.

- When sending a cold chain shipment, double check the cold chain plan and ensure that clear instructions are given to the transporter.

The shipper and the driver must sign the waybill and one copy must stay at the origin.

Documenting the consignment

- The transporter will leave with three copies of the waybill.

- Certain countries or regions will require the shipper to obtain a permit to access certain areas – make sure you request such permits from the relevant authorities.

- Keep a copy of the outbound waybill, to be reconciled with the returned signed copy after reception is confirmed by the receiver.

- Where delivery is planned directly at a usage point (a distribution point where no stocks are managed, for example), a GRN will have to be raised.

The delivery will not always happen at a warehouse, so a logistician should go to the delivery site and conduct the check of the delivered items and raise the GRN with the requestor of the goods.

Where goods are missing or damaged, the GRN will be returned with a filled-out claims form.

It is safer to ensure that drivers/pilots are issued with a mission order, confirming that they are moving humanitarian goods. A standard mission order should be available in each delegation/mission/project.

After dispatch

- Log the shipment in a shipment tracker, with details of the consignment. This will be used in the activity reporting process.

- Update your stock cards and bin cards (where relevant).

- Inform the receiver of revised expected time of arrival and confirm the transporter’s contact details.

- After receiving the returned signed copy of the waybill and GRN, where claims have been raised, make sure they are addressed, and that a corrective plan is in place to avoid future disruptions.

Read the next section on Shipping instructions here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates

Download full section here.

Some donors, destination countries and governmental bodies require that goods are inspected when they arrive in country, to ensure they have not been damaged in transit and that the goods entering the country match the customs declaration (shipping documents) and respect the quality standards imposed by the country.

There is a limited number of companies that provide inspection services and their rates are usually based on their local branches’ fees, transport fees and laboratories’ fees. These rates will often lack transparency and are hard to pass on to donors if they have not been pre-agreed in an approved budget, so it is important to include an assessment of the needs for inspection services in the review of the project design phase (see International Quality Methodology (IQM) guidance documents for more details on this). SGS and Intertek are the two major inspection service providers in the world.

Wherever possible, ensure that the inspection process is managed by either the selling or the shipping party, as they will manage the relationship with the service provider more effectively.

Inspection controls can also be required at departure. They are usually best managed by the selling party, but this is not always permitted, and donors or governments may have appointed independent inspection agents to sample and test some shipments.

Read the next section on Planning, tracking and reporting on transport here.

Download full section here.

Procuring for transport

Organisations often do not have the means to fulfil transportation requirements internally. The appropriate fleet might not be available, or the right skills may be difficult to source; knowledge of the local market, infrastructure or legal framework may also be scarce.

When transport requirements cannot be fulfilled with internal resources, they must be outsourced to professional companies. Transport service providers must be selected carefully, as they will be handling goods and materials owned by the organisation and, in most cases, distributing them to beneficiaries.

Be aware that in the context of crises or an increased humanitarian response, it might be difficult to source those services as competition for them increases. In those situations, it is recommended that organisations share the available resources by liaising with other Red Cross Movement partners to identify efficiency gains through sharing fleet.

Where operational, the Logistics Cluster can organise shared transport services on standard routes. Local/national authority coordination resources (such as the National Disaster Management Office) may also support resource-sharing where the Logistics Cluster is not mobilised.

Sourcing transport services

The supply chain strategy for a programme may include the procurement of vehicles to transport people and goods. Where this is not included, renting/leasing vehicles (and possibly drivers) will need to be considered.

In some contexts, a single service provider will be able to provide transport services for both goods and people, but in most cases two separate suppliers will have to be identified.

Selecting a transport service provider for the movement of people

For selecting a transport service provider for the movement of people, refer to the Procuring fleet: process, selection criteria, delivery section of the Fleet chapter.

Selecting a transport service provider for the movement of goods

Below are a set of criteria that should be considered when sourcing a transporter. Note that these criteria are particularly relevant in long-term agreements and less so where transport services are sourced ad hoc.

- Owns or has access to a bonded warehouse to protect and control shipments in transit.

- Is licensed by the government to conduct customs clearance formalities and is up to date on changes in customs regulations.

- Offers a variety of services (freight booking, re-packaging, clearance, etc.).

- Has influence in the transport market, with port authorities, etc..

- Has an established reputation; has been in business for a number of years.

- Has a proven record of reliability, accuracy, timeliness, as verified by customer references.

- Has experience working with humanitarian actors.

- Owns fleet for inland transport and has access to specialised vehicles when needed.

- Has trained, competent, experienced and trustworthy staff.

Transport needs assessment

Before going to market to source transport providers, it is recommended that you complete a needs assessment and to capture its result in the issued sourcing document (RFQ, tender or EOI – see the Sourcing for procurement section for details on the sourcing process). The needs assessment should detail the below requirements at minimum.

- nature of the goods to be moved

- any specific constraints relating to the type of goods

- expected delivery timeline and frequency

- expected delivery points

- cost coverage (fuel, maintenance, insurance, tolls, loading, driver per diem, etc.)

- compliance with Red Cross code of conduct

- cross-border requirements if applicable

- weight and volume of goods to be transported.

Assessing the local transport services’ market may include pre-qualification of service providers available. This will involve identifying as many potential suppliers as possible and asking them a series of questions to assess their suitability.

Depending on the expected volume of expenditure, and following applicable procurement procedures, an RFQ or RFP can then be sent to these pre-qualified suppliers with the details of the services needed.

Sourcing process

The sourcing document should clearly reflect the findings of the needs assessments and set out the selection criteria. For details on the recommended procurement processes, refer to the Procurement processes in the British Red Cross and Sourcing for procurement sections of the Manual.

Prior to the award of the contract, it is recommended to have face-to-face interviews with the successful supplier to review contractual terms such as:

- expected turnaround times (and any seasonal variations on this)

- cost per trip per load (if the routes are unlikely to change)

- contact focal points

- validity of quoted rates

- contract length

- payment terms

- penalties when agreed service standard is not reached.

Remember to select the right costing options for your needs – you can request a quotation per day, per type of vehicle, per ton or per route.

A template transport contract is available here and at the end of the section.

| Contract type | Details | Use when |

|---|---|---|

| Task-specific (one-off) | Quote based on set quantities, set schedule, set origin, set destination, limited timeframe | Needs are specific and limited in time and quantity There is a pre-defined budget for the service There is a single expression of needs (one requisition) |

| Open contract | Quote per vehicle type and per period (day, week, month) or per route | Long term projects with regular routes and needs Transport services market is stable and services can be scaled up and down There are multiple requestors for transport services |

Available to download here.

Transport service provider evaluation and performance management

It is important to agree evaluation criteria for the service provider’s performance monitoring, so the service provider has an opportunity to improve their performance across the duration of the contract.

It is good practice to hold quarterly meetings with regular service providers to review performance against set key performance indicators (KPIs). This requires careful recording of performance data on all shipments carried out by the service provider, a task that must be appropriately resourced internally.

Appropriate points of analysis and performance to evaluate transport service providers may include the below data points.

- total volume transported (weight, volume, value)

- per cent of shipments received on time in full (OTIF) per contractual schedules and damage definition

- number of claims raised, total value of claimed damages

- per cent of properly documented services (returned signed waybills etc)

- variations from contractual rates

- total spend to date against total value of contract (“burn-rate”)

- options to extend the value or duration of the contract

- actual availability of resources against contractually agreed availability (drivers, loaders, vehicles…).

Transport service providers can also be contracted for single operations, whether they involve a single transportation or multiple pick-ups and deliveries. In that case, the right selection and procurement processes must be followed for the estimated cost of the operation and the contract terms will slightly differ, as the costs and services will be pre-agreed. Penalties should still be agreed, but where the services required are to be completed over a short period of time (less than three months), the supplier performance review is limited.

Sourcing clearing agents

Clearing agents

Clearing agents can offer similar services to freight forwarders – they occasionally offer transport services from the point of entry into the destination country to the final delivery place. However, their “core” service offer is the clearance of goods through the destination country’s customs.

Clearing agents can be a valuable source of information in helping to anticipate issues that may arise during the customs clearance process.

In some countries, the government will impose a mandatory clearing agent; some shippers (senders/sellers) will offer services from a partner clearing agent in their quote, and some consignees (receivers) may recommend a partner clearing agent. Where clearing agents are recommended, it is usually good practice to use them rather than sourcing alternative agents. Where there are no suggested clearing agents, these must be sourced through a procurement process.

Selecting a clearing agent

The process and selection criteria are like those used when selecting a freight forwarder, with some more specific criteria to consider (that should have been identified in the transport needs assessment).

Below are some key requirements that should be included in the RFQ/EOI/tender document.

- is licensed by the government

- can handle road, air, sea shipments

- can provide details of procedures to follow for all types of goods ahead of shipment

- has offices located close to the entry points (port, airport, etc.)

- has access to a network of (bonded) warehouse

- can guarantee delivery to final destination

- has experience working with the humanitarian sector

- works with a network of licensed agents

- can share details of customers to provide references

- can share details of their client portfolio – contracting a clearing agent who will prioritise more important customers could be a critical risk to the delivery of supplies.

Sourcing a clearing agent

The sourcing document should also specify the criteria that will be used to evaluate the offer, some of which should be based on the list in the Selecting a clearing agent section above. As a result of responses to the above requirements, you may want to contract multiple clearing agents (one for air shipments and one for sea shipments, for example). You can also choose not to have contracts in place but a list of pre-qualified, pre-vetted agents, who would provide you with quotes on a shipment-by-shipment basis.

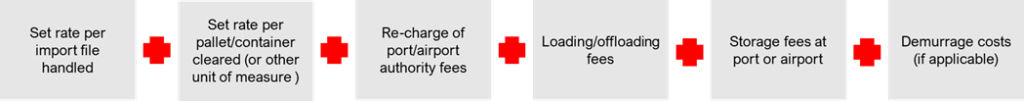

Note that the clearing agent’s fees structure is typically quite complex, and includes the following:

Remember to ask your clearing agent to provide the breakdown of the costs they forward to you in their invoices. Demurrage costs in particular should be clearly explained ahead of the clearing process.

Clearing agent evaluation and performance management

It is important to agree evaluation criteria for the clearing agent’s performance monitoring in the contract (or as an annex to the contract if they are linked to penalty fees). That way, the clearing agent will have a clear understanding of their client’s expectations and they are given an opportunity to improve their performance through the duration of the contract.

It is good practice to hold quarterly meetings, with regular reviews of performance against the KPIs that have been set. This requires a careful recording of performance data on all shipments carried out by the service provider, a task that must be appropriately resourced internally.

Appropriate key performance indicators to review clearing agents’ performance may include:

- average time taken to clear goods through customs (per mode of shipment), compared to contractually agreed time

- invoiced costs compared to quoted costs

- number of claims raised for losses or damages in transport and total value of claimed damage

- a review of cases where the process that was initially suggested had to be revised due to a lack of understanding of the specifics of the cargo

- demurrage costs incurred.

Note: demurrage costs are charged by port or airport authorities when shipments stay on their premises beyond an agreed number of days. They can add up very quickly as they are usually formulated per container or per pallet and incurred daily. They can be avoided through pre-defined agreements or preferential arrangements between clearing agents and port or airport authorities. They should be paid by the party responsible for the delay, but they are extremely difficult to waive once incurred.

Working with clearing agents

To process a shipment through customs, the sender or receiver of the goods (depending on the incoterm in place) will generally have to submit the shipping documents to the clearing agent in advance of the arrival of the cargo.

The type of documents understood by “shipping documents” will vary from shipment to shipment but will almost always include:

| Document | Function | Provided by |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial or pro-forma invoice | Declare total value of goods to be cleared | Seller |

| Packing list | Provide physical details of consignment and detailed contents | Shipper if sold EXW Seller if sold on any other incoterm |

| Donation or gift certificate (if relevant) | Declare 0-value of goods to be cleared and allocate ownership of goods to consignee | Shipper |

| Certificate of origin | Declare origin of goods | Manufacturer/seller |

| Certificate of analysis | Provide quality assurance certificate | Manufacturer/seller |

| Good Manufacturing Practices certificate (GMP) | Provide quality assurance certificate | Manufacturer/seller |

| Draft and final shipping title | Provide quality assurance certificate | Shipper if sold EXW Seller if sold on any other incoterm |

Available to download here.

Note: a gift certificate template is available in the resources for this section.

Read the next section on Sourcing inspection services here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Road, air, rail, sea and animal

Below is a matrix to assist with the selection of the most appropriate mode of transport:

Ratings are from one to five, where one is the strongest at the individual criterion.

| Speed | Reliability | Cost | Flexibility | Safety | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | Limited network Limited capacity in crisis |

| Sea | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | Restricted network Long admin delays |

| Road | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | Extensive networks Sensitivity to network condition |

| Rail | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | Fixed networks, routes and schedules |

| Animal | Depends on distance | Depends on distance | Depends on distance | 1 | 5 | Contracting can be challenging Consider how to add RC visibility |

Available to download here.

Choosing modes of transport and designing a strategy around it

In both local and international transport operations, the objective should always be to optimise the utilisation of resources used. This is easier to achieve in large international shipments than in the local management of transport, where there are usually multiple delivery points and sizes can vary widely.

In general, the objectives will always be to maximise the load being moved and minimise distances travelled and loading/offloading time, at a total cost that delivers value for money (VfM). However, factors influencing the optimisation process vary from one type of transportation to another.

Factors to consider include:

- local labour regulations (e.g., legal working hours for drivers)

- local security regulations (e.g., legal driving hours, curfews, checkpoints)

- delivery point characteristics and access constraints

- vehicle and fleet characteristics: available vehicles and their total/individual capacity

- environmental considerations

- available budget for transportation.

The transport chosen will depend on multiple factors.

Accessibility

- security issues

- delivery timeline and other programme imperatives

- transport infrastructure available, from origin to delivery point

- export/import customs regulations

- access conditions.

Cost factors

- distance and journey time

- weight and volume of goods

- funding available

- delivery schedule (especially in emergency)

- demand for transport (with limited supply, cost is likely to increase).

Donor compliance

- Some donors will impose a maximum ratio of cost of transport to cost of items as a performance indicator

- Some donors will not fund air transportation – transport must then be arranged earlier.

Others

- Dangerous goods require special transport methods or bring constraints (air freight regulations).

- Certain items require refrigeration in transit.

- Cross-border transport may impose restrictions on vehicle/driver based on nationality.

Read the next section on Procuring and sourcing for transport here.

Download the full section here.

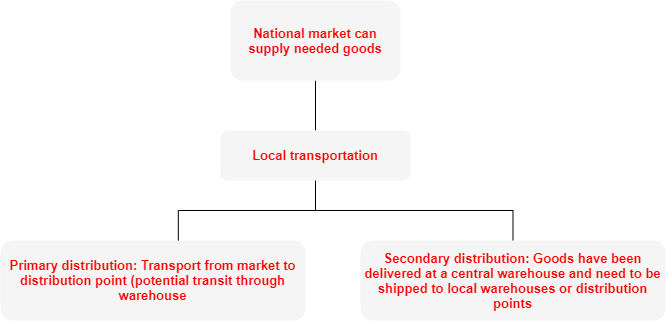

Local transportation is often required in countries where the national market can supply goods for the purpose of the ongoing programmes, in which case transport is from market to distribution point, with potential transit through a local warehouse (also known as ‘primary distribution’).

Local transportation is also required when goods have been delivered in country at a central warehouse and need to be further distributed to smaller regional or local warehouses, or distribution points. Sometimes these delivery points are served by a single transport movement; this is called “secondary distribution”.

Primary distribution

Primary distribution is usually straightforward and can be organised either by the selling party or the buyer of the goods.

For fragile loads, refrigerated goods or controlled supplies (chemicals, drugs, etc.) it is often better to leave the organisation of the transport to the seller, who will have a better understanding of the safety or regulatory requirements and a knowledgeable network of transporters.

For general supplies with no specific requirement, the buyer can organise transportation, either mobilising their own resources or outsourced fleet (rented trucks or chartered flights, for example).

Secondary distribution

Secondary distribution often requires more in-depth planning, to avoid wastage of time and resources.

Optimisation factors will include:

- Route definition: sequencing the deliveries in a way that minimises the use of fuel and lead times.

- Vehicle load: load in order of distribution, to minimise offloading time.

- Local context: considering labour laws and security rules (maximum number of hours worked, curfews).

- Safety and security: planning for safe overnight arrangements when the distribution route spans several days.

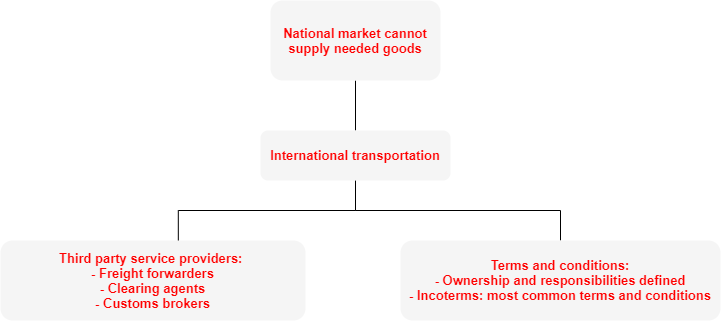

Specifics of international movements

International movements involve transportation from the origin country to the destination country, via ports, roads, airports or train stations.

Moving goods internationally will require interventions of third parties such as customs officials, clearing agents who may be required to support the customs clearance process, and freight forwarders who may be needed in case the sending or receiving party cannot supply the necessary vehicles.

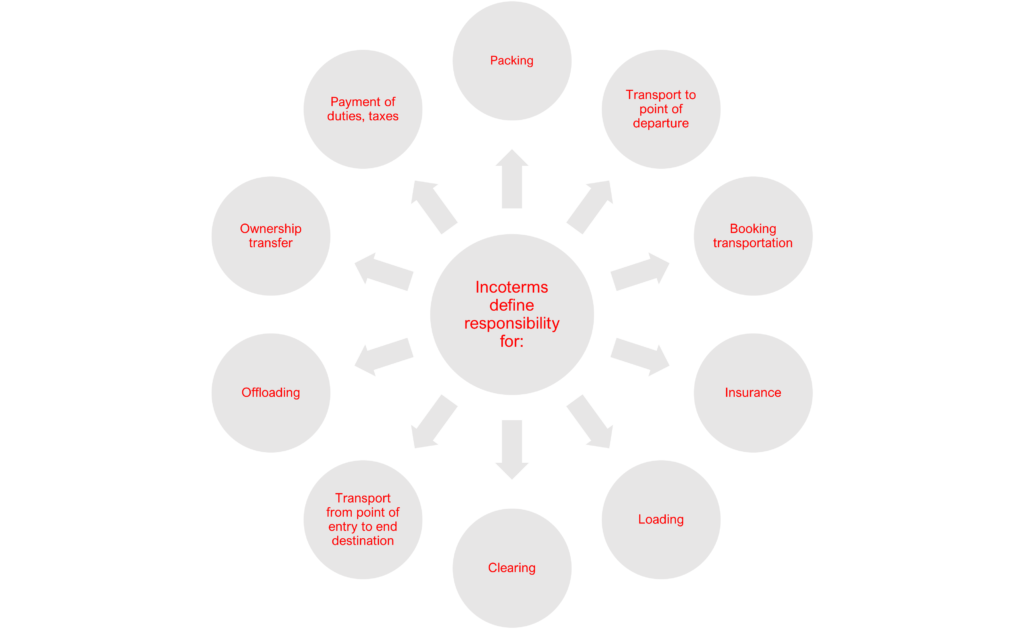

International shipments are usually arranged as part of the sourcing or contracting process under specific terms and conditions, commonly known as incoterms, or International Commerce Terms. Click here to access a guide to Incoterms and a summary table.

Incoterms are defined by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and are a series of pre-defined commercial terms that ensure sellers, shippers and buyers have a shared understanding of the commercial terms governing the commercial transactions they enter.

The agreed-upon incoterm will determine several conditions of the sale but most importantly, it will define who has responsibility (over costs and process) of:

- preparing the consignment for export (palletising, labelling, marking, wrapping, etc)

- carrying the consignment from seller to point of departure (port or airport)

- arranging and booking transportation services

- insuring the goods – up to which point will the goods be covered by the seller’s insurance and from which point will they be covered by the buyer’s insurance?

- loading the goods at point of departure and offloading at point of arrival

- clearing the goods through customs at point of arrival

- transporting the goods from point of arrival to point of delivery

- offloading at point of delivery

- defining when the ownership of the goods transfers from the supplier to the buyer

- clarification of who carries responsibility for payment of import duties, taxes, etc.

Planning for all of the above and selecting the right incoterm will avoid surprises during the transportation of the goods.

For a list of the most up-to-date incoterms, see the ICC website or the incoterms guide or summary table.

Read the next section on Modes of shipment here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates

Download the full section here.

Transport

Origin and destination

Learn more in the Types of movements: local and international section.

People and goods

Learn more in the Types of movements: local and international section.

Local and international

Learn more in the Types of movements: local and international section.

Air, sea, road, rail, other

Learn more in the Modes of shipment section.

How to select the best transport mode

Learn more in the Modes of shipment section.

How to contract transport services and how to monitor performance of transport services

Learn more in the Procuring and sourcing for transport, Sourcing transport services, Sourcing clearing agents and Sourcing inspection services sections.

Standard transport documentation

Learn more in the Shipping instructions and Transport documentation sections.

Transport data analysis

Learn more in the Transport data analysis section.

Elements of the transport of people can be found in the Fleet chapter.