All the processes detailed in this chapter relate to the management of British Red Cross’ international fleet.

For policies applicable to vehicles in use in the UK, refer to the page on RedRoom dedicated to fleet management by searching for “information about our vehicles” on the Redroom search bar).

The British Red Cross also has a maintenance of British Red Cross vehicles policy that applies to British Red Cross vehicles being driven in the UK.

Read the next chapter on British Red Cross globally pre-positioned stocks here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

View and download a list of documents to be kept in vehicle files for vehicles purchased through and purchased locally here.

Beyond the vehicle files, the below documents must be kept in the fleet files:

- copies of all mission orders

- copies of fuel procurement contracts or purchase receipts

- drivers’ files, containing driving licenses, training records, driver authorisation forms, signed rules and regulations forms, disciplinary procedure records.

Read the next section on British Red Cross domestic fleet management systems and procedures here.

Download the full section here.

Handover, disposal, sale, donation

For details on the asset disposal process, refer to the Asset disposal section.

Vehicle Rental Programme-owned vehicles may only be disposed of following approval and instruction from the regional fleet coordinator or fleet base. When the vehicle’s disposal has been approved, the IFRC fleet management team will provide an asset disposal form.

Additional requirements when disposing of vehicles may include:

- Donor requirements must be fulfilled, including the approval to dispose of the vehicle, generator or handling equipment.

- All radio equipment and visibility items (stickers, paintings and other markings) must be removed from the vehicle prior to its disposal.

- License plates must be removed from the vehicle, and its buyer or receiver must source new plates by following the registration process.

- No vehicle may be sold to military, paramilitary or state-affiliated organisations.

- The disposal of vehicles by sale, donation or scrapping is usually strictly controlled by local authorities, and the procedures to follow will vary depending on the importation status of the vehicle (see the Vehicle registration process section of Vehicle usage for more details).

- A vehicle handover form and a certificate of de-registration must be completed, in addition to a transferral or cancellation of the insurance policy (and a donation certificate where applicable).

- All documentation relating to the donation or sale of the vehicle must be kept in its file.

Vehicles that have reached their end of life in IFRC criteria should not be sold or donated to a National Society.

| Type of vehicle | Distance to end of life | Age to end of life |

|---|---|---|

| Light vehicles | More than 125,000km | 5 years |

| Heavy goods vehicles | More than 300,000km | No age limit |

Vehicle disposal checklist

Where the vehicles are donated, the donation process detailed in the Donating an asset to other organisations section of Asset donations should be followed.

Where the asset disposal form suggests the sale of vehicles, step-by-step guidelines for the sale of vehicles by competitive bidding should be followed, using the templates provided for publication of the invitation to bid, the provision of bids and for the contract of sale and bill of sale.

Read the next section on Fleet audit trail here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Vehicle registration process

All vehicles must be registered in their country of operation, in compliance with local law.

Vehicles (and larger generators) must be registered and insured before they can be considered operational. The registration process depends on the circumstances in which the vehicle arrives in the operation:

- The vehicle is imported new, with no previous registration records.

- The vehicle comes with export plates from the country of dispatch (which may or may not be the country of origin). Export plates usually have limited validity.

- The vehicle is still fully registered in the country of dispatch.

- The vehicle is already deregistered in the country of dispatch.

- The vehicle is registered in a third country.

Import procedures must usually be completed and the vehicle must be customs cleared before it can be registered. In addition to the customs clearance certificate, the below documents will be required:

- invoice

- packing list

- certificate of origin

- vehicle gift certificate (if applicable).

Only a partner with legal status in the country of operation can register a vehicle in their name. Therefore, vehicles used in an operation will usually be registered under the name of the or the , unless collaborating have legal status in the country of operation.

Note: generators and handling equipment do not usually require registration but this can vary between countries.

Insurance

Only a partner with legal status in country of operation can subscribe to an insurance policy. Therefore, vehicles used in an operation will usually be insured under the name of the or the , unless collaborating have legal status in the country of operation.

Vehicles rented through the (see the section on the IFRC vehicle rental programme) will be included in the IFRC global insurance policy, but additional insurance policies must be subscribed to locally, as applicable (these are usually third-party, theft and accident).

Refer to the VRP agreement for more details on insurance claims and payable excesses.

A Federation operation may register vehicles for insurance on behalf of a PNS under the following conditions:

- A fixed asset registration form is submitted and IFRC operation obtains approval from global fleet base.

- The PNS signs an integration agreement with the operation.

- The PNS agrees to respect the IFRC’s standard operating procedure, as laid out in the IFRC fleet manual.

- All PNS drivers are tested and sign the operation’s driving rules and regulations.

- Only drivers with a valid authorisation issued by the head of the IFRC operation may drive the vehicles.

Note: vehicles owned by a PNS and registered under the IFRC are subsequently covered by all IFRC insurance policies.

Tracking vehicle and generator use

For accountability and safety purposes, the use of fleet in an operation must be monitored. It is recommended that regular training is conducted, with refresher training for fleet users and spot checks on the correct use of logbooks.

Vehicle logbooks

Every vehicle operated by the British Red Cross, including rented vehicles, must have an allocated vehicle logbook to monitor the use of the vehicle, refuelling and maintenance.

Every movement of the vehicle must be captured in the logbook, which is an auditable document.

Every entry in the logbook must be signed by the driver (for refuelling), the passenger (for trips) or the fleet manager (for maintenance services).

Where vehicle costs are charged to specific cost codes or programmes, these must be recorded in the logbook, with the passenger or cargo details.

Note: when cargo is transported, reference must be made in the logbook to the waybill associated with the load transported.

Generator and handling equipment logbooks

The use of generators and other handling equipment such as forklifts must also be monitored and auditable. Running hours must be captured in a logbook. Details to be included in the generator and handling equipment logbook include:

- every period of usage (running hours) – signed off by the user in charge

- refuelling – signed off by the person in charge

- maintenance services – signed off by the fleet manager or mechanic (as applicable).

The generator (or equipment) handbook must be controlled by the logistics lead at regular, pre-agreed intervals. The logistics lead should sign or initial pages after each regular check.

Generators and handling equipment should normally be allocated to a specific cost code or programme. Where that is not the case, details of the recharge must be indicated on the logbook.

Safety and security

General vehicle safety

Fleet procedures and road safety policies are in place to ensure maximum security for drivers, passengers, and vehicles, and must be adhered to.

All vehicles must be mechanically sound and roadworthy. Fuel, tyres (including the spare), water, coolant, brake fluid, steering fluid and oil levels must be checked regularly.

Refuelling should be optimised so that a vehicle’s tank is always at least half full.

Depending on context, all vehicles should be equipped with communication equipment, emergency repair materials (spare tyres, jump leads, vehicle jacks), passenger safety equipment (safety belt, drinking water), accident preparedness equipment (first aid kit, fire extinguisher, list of contact numbers). All vehicles must be equipped with Red Cross markings, including emblem and no weapons sign.

As per the Asset maintenance section, inspection and maintenance must be planned, conducted, and documented, in order to ensure that vehicles and generators are safe and efficient.

The driver of a vehicle is responsible for checking the condition of their vehicle and all necessary equipment in the vehicle, while the facilities manager is responsible for checking the condition of generators.

View a list of elements that make up a good driver here.

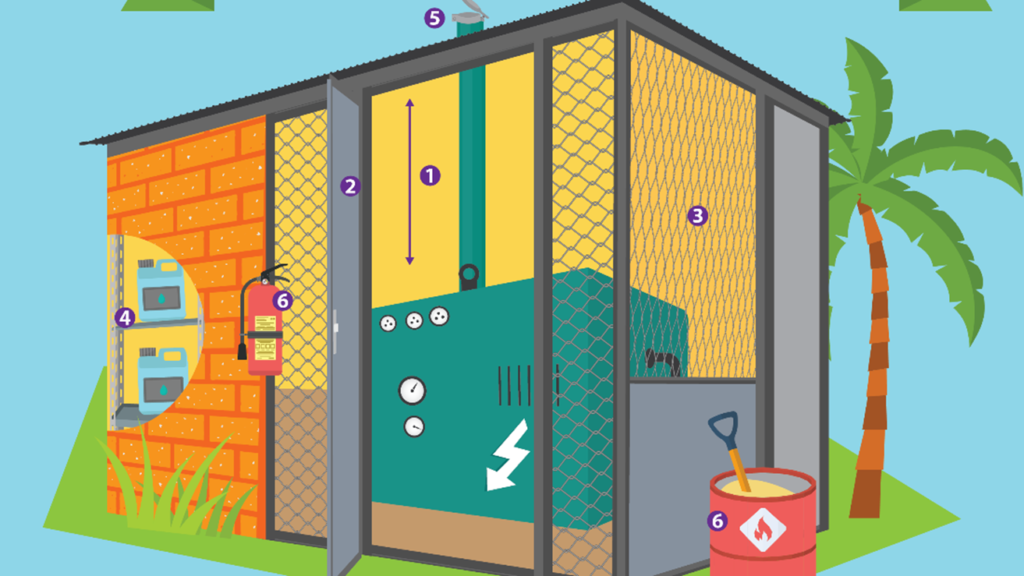

Using generators safely

Where generators are used as back-up power or a primary power supply system, the below recommendations will ensure safe usage of the units.

Generator sheds (see the example design below) are recommended to limit access to the generator and protect humans and animals. It also ensures that only one person oversees the maintenance of the generator.

- Distance between the top of generator and the ceiling is a minimum of 1.5 metres to ensure good ventilation and access for maintenance. Around one metre is required around the generators and between two generators.

- There is a well-secured area with a lockable gate, blocked from weeds growing in but sufficiently open to let gas escape.

- There are enough openings in the structure to allow good ventilation, both at the bottom and the top.

- There is sufficient space for the storage of oil, funnels etc. Fuel should not be stored in the generator room/shed.

- There is an exhaust outside the structure, protected from rain and a straight pipe without sharp angles.

- There is firefighting equipment – an ABC-type fire extinguisher and a bucket of sand with a shovel as a minimum.

Generator safety basics:

Set-up

- Ensure the ground (or preferably the concrete foundation) is strong enough to hold the weight of the generator.

- Elevate the generator by 10–20cm above the ground to prevent it from flooding.

- In very hot conditions, generators might overheat. A running schedule should be used to allow the generator to cool down. Do not open the doors of the generators while it is running, as this disables the cooling function.

Usage

- Do not daisy chain extension cables, as they will melt.

- Do not overload the generator by connecting too many appliances at the same time. See appliances’ kVa rates table in the Power supply section.

- Make sure a grounding pin is properly installed to the generator, and that all the cables and appliances have a connection with grounding.

ICRC convoy procedures

When operating in the field, the and other Movement partners often travel in convoys. Because of the nature of ICRC operations, unarmed and in conflict situations, humanitarian personnel often travel in a group of vehicles, for protection purposes. The head of delegation decides in what situations this is necessary.

The aim of the ICRC Convoy Procedure document is to provide guidelines to staff organising or joining convoys. The list of responsibilities is designed to help conveyors and drivers in the field, before, during and after a convoy.

British Red Cross driving procedure

The British Red Cross has a Driving in the British Red Cross policy that must be adhered to when driving a British Red Cross vehicle in the UK.

When driving a British Red Cross vehicle outside the UK, the agency with security lead (the , or ) provides driver regulations. It is the responsibility of every British Red Cross delegate to enquire about applicable driver regulations when joining a Red Cross operation.

Provided that they have passed the driving test and hold an official driving license, delegates may be allowed to use vehicles for personal use. However, rules applying to the personal use of vehicles will vary depending on the context of the operation, and advice should be sought from the IFRC or the HNS.

In some operations, the personal use of fuel will be recharged to delegates.

Note: logbooks must be kept up to date for personal as well as professional use.

IFRC driver rules and regulations

All personnel deployed within the must read and sign a copy of the operation’s driver rules and regulations form before they are authorised to drive a Federation vehicle.

The form sets out both country-specific rules and standard operating procedure for the use of Federation vehicles. A signed copy of the form will be kept in the staff member’s personnel file.

The default position on IFRC and other Red Cross missions is that delegates are not allowed to drive themselves, unless the country-specific driver rules and regulations allow it. Medical evacuations and security situations are treated as exceptions to that position.

The standard driver rules and regulations form must be adjusted to reflect country-specific conditions. The head of operation for a Federation operation, the head of project for a operation or the secretary general for a National Society operation determines the country-specific rules concerning vehicle use (for example, conditions for and limitations on delegate driving, mission order procedures, country-specific security regulations, etc).

The fleet manager or delegated authority must ensure that all vehicle users are aware of Federation procedures and country-specific rules, as well as local driving regulations and conditions.

All drivers, including delegates, must have a valid driver authorisation form, signed by the head of operation and the fleet manager, before they are permitted to drive a Federation vehicle. The authorisation must specify the types of vehicles permitted and any limitations on their use.

Note: passengers are restricted to National Society personnel (volunteers and staff), IFRC and staff. Members of UN agencies and other NGOs are permitted as passengers, as long as travel is within the scope of the Movement’s activities. Transporting other passengers or cargo is not allowed, except with previous authorisation from the IFRC country representative or staff in charge of managing local security (for example, programme manager, ops lead, etc).

All drivers, including delegates, must undertake a test of driving ability in their country of station or deployment.

British Red Cross safety training pathway

Refer to the Safety training pathway section in the Warehousing chapter.

Planning for usage

A well-sized fleet should aim for maximum usage, with minimum “idle” time and maximum availability for requests, with minimum service interruption or “down-time”.

Requesting a vehicle and cost recharge

To ensure vehicles are consistently available and sufficient for an operation’s needs, with a minimum number of vehicles underused, a request system that is as simple as possible and as complex as necessary will be helpful.

There are multiple ways in which users can request vehicles:

Vehicle whiteboard – used on a daily basis, listing all available vehicles. Requestors write their name and department on the whiteboard, with trip details (destination, departure time, number of passengers, estimated duration).

Vehicle requests should ideally be recorded at the end of the week for the next week, with an agreed level of flexibility for unforeseen circumstances.

Vehicle request form – submitted to the fleet manager or dispatcher within an agreed timeframe before the vehicle is needed.

Cargo transport request form – for the transportation of goods within an authorised area.

If the transport request is to locations outside of the authorised area, it should be accompanied by a mission order.

These methods are applicable to cases where vehicles are needed for local movements on a single day. Longer trips outside of the operating area or multiple-day trips must typically be approved through a field trip form or mission order, which requires sign-off from line manager, fleet manager and potentially the security manager (depending on context).

Vehicles are usually managed as a pool by the logistics department. Other departments can request to use vehicles, usually on a daily basis, and their usage can be recharged to the requestor through the pool management system.

Vehicles can also be fully allocated to a specific budget, with all costs related to them, including driver, fuel, maintenance and insurance, charged to that budget.

Note: logistics usually has budget to cover fleet maintenance costs, but unusual maintenance services can be charged to requesting departments as applicable.

Fleet productivity: utilisation and performance

In order to review the size of the fleet, monitor usage and report on fleet performance, it is recommended to track productivity in different dimensions.

Fleet performance can be measured looking at:

- Utilisation – resource used (number of vehicles used over period) divided by the available resource (total number of vehicles available over the period). Expressed as a percentage:

No. of vehicles used over the period ÷ total no. of vehicles available over the period = fleet utilisation as a percentage.

- Performance – actual tonnage (or passengers) moved divided by total tonnage (or passenger space) available in a period. Expressed as a percentage:

Tons transported over the period ÷ total tons available to transport over the period= fleet performance as a percentage.

Vehicles’ performance can be measured looking at:

- Utilisation – number of days/hours used divided by the total number of days/hours in a period. Expressed as a percentage:

No. of days or hours vehicles was used over the period ÷ total number of hours or days in the period = vehicle utilisation as a percentage.

- Performance – number of days available for used/total number of days in a period. Expressed as a percentage:

No. of days in the period that the vehicle was available ÷ total no. of days in the period = vehicle performance as a percentage.

Note: where the vehicle’s performance is <80 per cent, the vehicle is not performing well enough and should either be replaced or given a revision.

- Downtime: days that a given vehicle is not available for operations, due to planned or unplanned maintenance (ideally the split between planned and unplanned should be detailed).

Where no logistics staff are available, country representatives/delegates should seek support from , or logistics coordinators to compile the fleet performance data.

For more details on reporting for fleet, see the Reporting on fleet section.

Read the next section on Managing fleet here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Budgeting for fleet

Fleet management budgets should include the full costs associated with running fleet, including:

- cost of vehicle acquisition (buying, rental costs)

- cost of fuel, service and maintenance

- shipping costs associated with the acquisition or return of vehicle (including import tax, if applicable)

- disposal costs (at the end of the programme)

- insurance costs

- registration and licensing costs

- drivers’ costs (include per diems for field trips)

- other staff costs associated with managing the fleet (e.g. dispatchers, mechanics)

- costs of additional equipment associated with the fleet, including vehicle radios, first aid kits, fire extinguishers, alarm systems and tracking systems.

Fleet management typically includes fixed costs and running costs.

Fixed costs: (One-off costs to make fleet available to the operation)

- vehicle/generator

- import costs (if applicable)

- in-country registration cost

- end-of-life sale income.

Running costs: (recurring costs to maintain availability of fleet for use)

- driver costs

- maintenance

- spare parts

- fuel

- insurance

- depreciation

- parking fees and tolls

- revision costs and renewal of roadworthiness certificate (where applicable).

When budgeting for fleet, both cost types must be included in the budget (preferably separately), and expenses against each must be tracked, reported and analysed in monthly reports.

It is helpful to consult with offices or the regarding information about fixed costs, as they will have data from past operations.

For vehicles supplied via the , monthly reports are required to be submitted to the IFRC fleet base (usually via their ‘FleetWave’ system) – the required data forms part of the VRP contract.

Note: data for the monthly logistics reports should be provided by finance, but the logistics or fleet unit are responsible for checking the reported expenses against approved purchases, maintenance orders or fuel requests.

Procuring fleet: process, selection criteria, delivery

In general, it is recommended to use existing framework agreements (FWAs) to purchase vehicles (FWAs can be held globally by the or , or locally by the ) as this allows centralised purchasing and management, and economies of scale.

Where there are no FWAs in place, the procurement of fleet will generally be done through a tender process, due to the high value of the acquisitions.

Refer to the procurement chapter for details on the tender process, in particular the Tendering for goods or services and Using the Movement’s resources sections.

Fleet-specific considerations when tendering for vehicles:

- Ensure that a registered Movement partner in country (IFRC/HNS) agrees to be the buyer and legal owner of the vehicles, and include them in the tender process.

- The committee on contract (CoC) should include representatives from the legal buyers (IFRC/HNS) and the funding partners. Technical experts and end users should be represented on the CoC too (ask logistics coordinators if necessary).

- The tender response document must specify the origin of the vehicles, their year of manufacture, current mileage, service history and warranty details (if purchasing second-hand).

- Specify in the tender document whether the purchasing organisation is exempt from paying import taxes and duties.

- The tender response document should include a breakdown of costs: vehicle, options, import fees and registration fees.

- Specifications* must be developed per standards, preferably with input from expected users and logistics experts. It is strongly recommended to consult British Red Cross UKO team. Specifications must be as detailed as possible.

- Submissions to the tender must include an ownership certificate from the current owner of the vehicles.

*For specifications, see the Fleet options and modalities section of Defining fleet needs.

Options to avoid if possible:

- Electronic systems that are too sophisticated.

- Automatic transmission is to be considered only if there are competency restrictions with manual transmission.

- Specifications with risk of adverse perceptions, such as tinted windows or leather seats.

- Vehicles that are non-compliant with local and national emission regulations.

Note: buying second-hand vehicles is not permitted by all donors – check with your programme team which procurement rules apply under the funding used.

HR resources for fleet

The staff required to run the operational fleet depends on the size of the fleet, the number of daily vehicle movements and the operational context of the project.

| Fleet size | No. of vehicles | Recommended HR structure |

|---|---|---|

| Small | 1 - 5 | Admin delegate with senior driver |

| Medium | 6 - 29 | Fleet manager and vehicle dispatcher |

| Large | > 30 | Fleet delegate with full team |

Available to download here.

The operation should align budgets to activity levels to determine the fleet department’s resourcing structure. The following are roles to consider in a fleet team:

- vehicle drivers

- dispatchers

- fleet supervisors (or head driver)

- fleet managers

- fleet assistants

- radio room staff

- mechanics.

Standard role descriptions, with detailed competency and tier requirements, are available from the UK-based logs team.

Read the next section on Vehicle usage here.

Download the full section here.

Available to download here.

Note: operational constraints include security context and regulations that may apply (import options, labour law, etc).

Vehicles

The number and type of vehicles should always be aligned to the operational needs and conditions, including security, terrain, and team movement patterns. Operational fleet decisions must be compliant with safety and security guidelines (as stated in the IFRC Fleet Manual), with any deviation requiring approval from .

The vehicles selected must comply with IFRC standards, unless approval for the use of non-standard vehicles has been obtained from UKO.

When selecting vehicles, consideration should be given to the following factors:

- local terrain and topography

- state of road and traffic infrastructure

- need for specific equipment, such as in-vehicle communications equipment, a tow-bar or winching equipment, or use of the vehicle as ambulance

- import and export regulations

- local driver capacity (automatic or manual driving, 4×4 driving, left or right-hand drive)

- distance to be travelled and estimated usage (frequency, payload, etc)

- compatibility with existing fleet composition

- local and national service/maintenance and the availability of spare parts

- local rules and regulations, including emission regulations (not all IFRC-standard vehicles meet current emission levels for all countries)

- climate, including seasonal change.

The IFRC standard products catalogue contains full technical specifications of Federation-standard vehicles.

The key point for organising fleet is knowing what the needs are for the programmes in the country office (including any sub-delegations) and for general operations. It is the role of logistics to analyse these needs and then optimise the fleet. This, combined with the national regulations (i.e. load limits for trucks) and the limitations of the surrounding area (i.e. infrastructure) will provide the necessary information to choose the most effective set-up of fleet.

Defining the number and type of vehicles depends on the volume of the workload and the material or number of passengers to be transported, as well as the distance and terrain covered.

The below table will help define the type of equipment needed in operations. To help calculate the number required of each type of vehicle, see Annex 9.1, vehicle set-up evaluation in the ICRC fleet management manual.

| Consider | Criteria | Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Type of terrain | Town/country/topography Paved/dirt roads Seasonality Warehouse Construction site | Cars, high-range 4x4, low-range 4x4, engine power Specifications of vehicles Tyres, sand plates, motorbikes, etc. Forklift Digger |

| Transport capacity | Bridge and road weight restrictions Local/international distribution Transport of passengers/cargo | Light trucks Trucks Bus |

| Radius of operation | Vehicle fuel capacity and reliability Number and type of vehicles Typical and exceptional journey durations Fuel quality and quantity in area of operation | Refuelling options, linked to typical and exceptional journeys (mileage and duration) Fuel sourcing strategy Storage on site |

| Availability of electricity | Power for all operations Security | Generators vs city power |

Each department has its own needs in terms of type and number of vehicles to add to the fleet list. For example:

- Administration may require cars for errands or official visits.

- Programme teams may need light 4×4 vehicles for field visits and transfers.

- Construction and warehousing teams may need pick-ups for equipment.

- Teams in charge of distribution (usually called relief team) will need trucks.

Combining and analysing these needs into a summary table will help constitute the fleet (in number and type), in a way that meets the needs of each team and minimises the cost of operation. The vehicle pool system (see the Requesting a vehicle and cost recharge section of Vehicle usage) should be considered, as it maximises vehicle utilisation through avoiding the taking of vehicles without justification.

| Team 1 | Team 2 | Team 3 | Team 4 | Team 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle type 1 | ||||||

| Vehicle type 2 | ||||||

| Vehicle type 3 | ||||||

| Vehicle type 4 | ||||||

| Total |

Available to download here.

Power supply

Generators must be set up and maintained by qualified staff – a mechanic or a head driver. Support is always available from locally available staff from other , or or from -based logisticians.

Note: specialist skills are required to manage generators. Staff involved in plant management processes must be trained electricians or experienced logisticians.

The output of a generator is measured in KvA (kilovolt-ampere) and volts. They can be air or water-cooled and can be soundproofed (silent) or not. Generators are either petrol or diesel-powered.

The British Red Cross uses hybrid generators when deploying their logistics or Emergency Response Unit teams (see the ERUs chapter for more details on the ERUs). These provide standard power generation and simultaneously charge a set of batteries, which can be used to provide power once the generator is turned off. The batteries’ power demand must therefore be included in the load calculations. Details of the generator specifications as well as a user manual are available from the international logistics team upon request and provided to the teams when they deploy.

It is important to match the power generated to your electrical needs as closely as possible: if the load is too high, the generator will stop and be damaged. But when the generator is supplying less than 40–50 per cent of its power capacity, fuel consumption increases, the lubricant deteriorates more quickly, and the engine’s life cycle is reduced.

Without any power demand to it, a generator will typically already be using 25-30 per cent of its rated power.

| Scenario | Impact on generator set | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Power demand is less than 40–50% of the maximum rated power | Fuel consumption increases Generator life cycle is reduced Lubricant deteriorates more quickly |

| B | Power demand is between 60–80% of maximum rated power | Optimal use of the generator |

| C | Power demand is more than 80% of the maximum rated power | Fuel consumption increases (but less than in Scenario A) |

| D | Power demand is more than 100% of the maximum rated power | Generator stops Generator life cycle is reduced |

Available to download here.

It is a good idea to have batteries as part of an electricity provision setup, so that they can be charged while the generator is turned on. Critical appliances (communication systems, fridges, alarm and/or security systems) can then work in case neither city power nor the generator can supply power. If the generator is used to charge batteries, make sure their rated kVA is calculated into the total power requirements.

To calculate your power supply needs and to choose the right generator, use the power calculator table. The generator size (in kVA) must be equal to or greater than the total consumption of all appliances. The higher starting requirement must be considered when calculating the generator size.

| Consider | Criteria | Decisions |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical load | Total load calculations Power (kVA) Local voltage and frequency | Reduce requirements? Alternate generators? (consider whether budget can cover duplicate setup) |

| Expected usage | Permanent/back-up system Consider requirement for UPS by way of back-up Starting system (manual/electric/automatic) | Alternate generators if constant power supply needed Establish running hours with regular breaks (consider if budget can cover duplicate setup) |

| Make, brand, place of manufacture | Local availability and quality of relevant fuel and parts Local maintenance capacity | Budget for fuel and spare parts |

| Geographical area of use | Altitude Temperature and weather conditions Exhaust emission regulations Cooling system (air/water) | Improve electrical safety at location Isolate generator appropriately (consider budget availability) |

| Place of use | Indoors/outdoors Ventilation Protection from elements Noise and disruption Type (portable/fixed/on trailer) Safety | Budget for generator shelter or noise reduction system Require inspection of terrain Security requirements How to earth it effectively? |

| Price | Budget, set-up costs, maintenance costs | Within budget/out of budget |

Available to download here.

Fleet options and modalities

The ’s aim regarding fleet management is to standardise fleet as much as possible, allowing for easier tracking, resource-sharing, and maintenance management. It also allows different parts of the Movement to benefit from competitive pricing from manufacturers.

Vehicles outside the list of standard fleet should only be purchased after approval from a centralised fleet management team (usually HQ logistics, or ).

The IFRC standard products catalogue and include the list of standard vehicles.

Fleet to be used in field operations should always be procured centrally and through the existing agreements with manufacturers.

Where fleet is being procured locally and only for city use, the following criteria should be adhered to as much as possible:

- Make – well-known European or Japanese make, well represented in country of operation.

- Category – city car (Peugeot 208, Toyota Corolla or equivalent), not necessarily a station wagon.

- Engine power – maximum 100 hp or 75 kw.

- On-board security – Alarm/immobiliser, antilock braking system (ABS), electronics stability control and air bag if available.

- Fuel – diesel or petrol (check regulations, availability and consider the environmental impact).

- Pollution control – optimum, but at least as per local regulation.

- Transmission – two-wheel drive, preferably automatic – unless road conditions in the city require four-wheel drive.

- Colour – preferably white, and a light colour if not available – should not clash with Movement visibility.

- Budget – equivalent to the cost of standard vehicles.

- Maintenance – access to local maintenance without HQ support.

Standardisation and compliance to environmental regulations should also be applied to the choice of generators. In general, ensure that the brand is well-established, that fuel type matches local fuel availability and that spare parts and maintenance are widely available.

Different types of fleet sourcing solutions

British Red Cross own fleet

In this option, the British Red Cross purchases the vehicles and uses them for its operations.

The decision of what vehicles and how many to buy will be based on operational needs and the procurement must be controlled and managed through . Such vehicles would be purchased and imported under the and the British Red Cross would donate the vehicles to them once the British Red Cross-supported programme ends.

This option would usually only be considered when:

- it represents better value for money than other options, such as using the ’s system

- vehicles are required for more than two years

- there is assurance that the donation does not place an unnecessary burden on the HNS in terms of maintenance and cost.

In these cases, the British Red Cross usually covers all the costs associated with the vehicles, including maintenance, drivers’ charges including per diems, local insurance, registration and fuel.

The maintenance of British Red Cross-purchased vehicles outside the UK is done following the IFRC maintenance guidelines, unless it is agreed that the vehicle is managed under the ‘ fleet management procedures.

Commercial rentals

Renting vehicles or outsourcing their maintenance can be a requirement for an operation either temporarily (during a short-term surge in activity) or as a long-term solution (where ownership is not an option).

If renting vehicles, the applicable procurement procedure should be followed. The selected rental company must be reputable and offer value for money. See the Sourcing for procurement section for more details.

IFRC vehicle rental programme

For step-by-step guidance on sourcing vehicles through the , refer to the VRP service request management/business process document.

The vehicle rental programme

The International Federation’s vehicle rental programme (VRP) was established in 1997 to ensure a cost-effective use of vehicles and fleet resources. Revised in 2004, it continues to be an effective means of providing vehicles to International Federation and National Society operations. The programme is run as a not-for-profit service within the International Federation; monthly vehicle rental charges are calculated to cover the vehicles and the operating costs of the VRP.

Depending on the estimated period of vehicles’ requirement, it may be cheaper or more straightforward to rent them through the VRP, but a full cost comparison should be done before a decision is made. Cost comparison must cover the cost of the vehicle, shipping, registration, insurance and local insurance, maintenance and PSR of 6.5 per cent.

The overall aim of the VRP is to provide good-quality vehicles as quickly as possible, and with maximum bulk discount. It also enhances standardisation, centralises control and minimises costs, through end-of-lease sale. Vehicles on this programme are managed through the fleet base in Dubai and remain the property of the . All leases must be organised through the IFRC.

The vehicle rental programme is managed through the global fleet base in Dubai, but a lot of the fleet management team’s responsibilities are delegated regionally and implemented through regional fleet coordinators in the Operational Logistics procurement and supply chain management units (OLPSCM, also known as Regional Logistics Units).

Note: monthly VRP invoices are processed through .

The VRP agreement is materialised through a vehicle request form, which must be signed off by the British Red Cross country manager and submitted to the global logistics service (GLS) team in Dubai.

Global fleet base vs regional units: roles and responsibilities

VRP system – roles and responsibilities are as follows:

Global fleet unit (Dubai)

- overall management (operational and financial)

- maintaining the VRP business plan

- procurement hub for vehicles and vehicle-related items

- managing all incoming requests for dispatch and allocation of new and used vehicles

- supporting disposal of VRP vehicles

- preparing vehicles for deployment (technical assessment and repairs).

Regional fleet coordinators (in )

- implementation and maintenance of standards at a regional level

- advise on the implementation of preventative maintenance and repairs to maximise lifespan and usage of regional fleet

- coordinate movement of fleet across the region

- supporting planning of transportation needs in the region

- implementing standard asset disposal procedures

- ensuring proper maintenance of fleet wave database and analysing data

- reporting on regional fleet usage to global fleet base

- maintaining regional fleet files

- advise and train on fleet sizing, fleet management and VRP

- managing regional IFRC fleet.

VRP rental costs

To encourage forward planning, cost incentives have been built into the . Rental rates are based on a sliding scale, in which longer rentals benefit from cost savings (i.e. a sliding scale, based on the duration of the contract).

| Model | Five-year average monthly cost (CHF) | 12-month average monthly cost (CHF) |

|---|---|---|

| Toyota Land Cruiser HZJ78 | 720 | 830 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser pick-up double cabin HZJ79 | 671 | 775 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser pick-up single cabin HZJ79 | 650 | 750 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser SWB HZJ76 | 736 | 850 |

| Toyota Land Cruiser Prado LJ150 | 696 | 800 |

| Toyota Corolla ZZE142 | 635 | TBC |

| Toyota Hiace minibus LH202 | 621 | 715 |

| Nissan Navara pick-up double cabin | 546 | 630 |

Available to download here.

These rates are indicative and may change – quotes can be requested from the global fleet team when considering renting vehicles through the VRP. The latest version of the rate sheet is available here.

An additional 6.5 per cent programme support recovery cost must be added to the total cost of the contract with the VRP, as well as delivery and return shipping costs (including any applicable import duties).

VRP system – cost structure

Included in VRP rental rate

- global third-party liability insurance cover (up to CHF 10 million)

- full vehicle damage insurance (including a replacement vehicle)

- vehicle replaced at the end of its lifetime

- fleet management support

- accident insurance for driver and passengers

- specialist driver training (depending on context and availability of funding)

- access to a web-based fleet management system.

Not included in VRP rental rate

- telecom equipment ordered by the operation

- additional equipment: snow chains, spare part kits, roof rack

- all charges linked to the delivery of a vehicle: shipping, in-county transport, customs duties, taxes for import, port and warehouse charges, etc

- all in-country charges: registration, vehicle insurance, local third-party liability insurance, etc

- all operating costs, including fuel, maintenance and repairs

- all charges linked to the return of the vehicle to a VRP stock centre or secondary destination (as requested by global fleet base): customs duties and taxes for re-export, cost to deregister the vehicle in-country, transportation, port and warehouse charges, etc.

- any costs for additional repairs resulting from the loss of or improper documentation relating to a vehicle’s maintenance history

- any costs for additional repairs at the end of the rental period, for damage considered beyond the normal wear and tear.

Using another National Society’s vehicles

Most National Societies (NS) use a mileage rate that they charge for the use of their vehicles by Partner National Societies (PNS). Alternatively, they may charge a monthly fee or let PNS use their vehicles and only charge them the cost of fuel.

Mileage rates and what they include often differ, and it is recommended to clarify what is covered (fuel, driver costs, maintenance, etc), and how the amounts to be recharged will be calculated.

Choosing the best vehicle ownership solution

British Red Cross owned vehicles

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Vehicles belong to British Red Cross.

- At the end of a project, these can be disposed and realise residual value.

- British Red Cross is free to donate these vehicles to any partner of choice after the end of a project or five years.

Risks for British Red Cross

- British Red Cross must source the vehicles and ship to operation where required.

- Some governments force international organisations to donate vehicles to their governments at the end of a project.

- Vehicle must be managed as an asset (including depreciation).

- British Red Cross must spend large sum to buy the vehicles outright.

- If mission is cancelled or discontinued at short notice, British Red Cross is stuck with these vehicles.

- It is difficult to increase/reduce fleet size at short notice, but surge option plans can be built in.

- Donor constraints on expenditure.

IFRC’s vehicle rental programme

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Monthly vehicles rental cost is known, so easy for budgeting purposes.

- Access to standard vehicles.

- There is good scalability of fleet.

- Vehicles comprehensively insured at global level by IFRC.

- IFRC will replace vehicles after 150,000km or five years, whichever comes first (in-country costs associated to vehicle change will need to be covered by the requesting , but all other costs covered by ).

- IFRC will provide fleet management support, including cost tracking and driver training.

- There is no cost of disposal.

Risks for British Red Cross

- Solution includes shipping the vehicle into operation area and shipping out after the end of the lease, which can delay the availability of the vehicle to the operation.

- After five years, vehicle still belongs to IFRC and British Red Cross cannot donate it to partners.

- It can be expensive in the short term, considering shipping costs into and out of operational area.

- IFRC will charge a programme support recovery fee.

Local vehicle rental

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Locally available and no importation costs or delays.

- It is easy to scale up or down.

- It is easy to arrange at short notice.

- It supports the local market.

- Budgeting is easier when rates (including maintenance and service) are fixed.

- There is no need to have own maintenance facilities or resources.

Risks for British Red Cross

- Rental rates can be very high.

- There may be a maximum mileage under the rental scheme.

- Locally available vehicles may not be of a good standard.

- Local maintenance practices may not be safe.

- The right vehicles are not always locally available.

- Renting vehicles from questionable business people could result in bad reputation by association. Consult international sanctions lists before entering a lease agreement.

Using other National Societies’ vehicles

Benefits for British Red Cross

- Vehicles are readily available and easy to scale down.

- It gives support to movement partner.

Risks for British Red Cross

- It is not always easy to scale up (they might not have enough vehicles).

- It is only possible with small requirements.

- Vehicles are not always of a good standard.

- British Red Cross can only use what the partner has excess of or does not require.

Read the next section on Resourcing for fleet management here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

In this chapter, “fleet” will be used as a generic term for any piece of equipment fitted with an engine, including vehicles, motorcycles and power generators.

Types of vehicles

This chapter will cover the use of passenger vehicles and cargo vehicles equipped with engines, as well as utility vehicles.

Light fleet – all vehicles weighing up to 3.5 tonnes, including passenger cars, pick-up trucks, small trucks, minibuses up to 16-seaters.

Passenger vehicles – buses with over 16-passenger capacity.

Heavy duty trucks – buses with over 16-passenger capacity.

Construction and mechanical handling equipment – including tractors, forklifts, diggers.

Motorcycles – two-wheeled or three-wheeled motorised vehicles.

Types of generators

Where power is not available through a publicly maintained network, generators may be necessary as a temporary or permanent source of power. A variety of generators are available, which can make the selection process complicated.

A generator is generally composed of an electrical generator (the alternator) and an engine (or prime mover), in a single piece of equipment.

For more details on types of generators and how to use them, see the Power supply section of Defining fleet needs.

Read the next section on Defining fleet needs here.

Download the full section here.

Fleet

Definitions

Learn more in the Definition of fleet section.

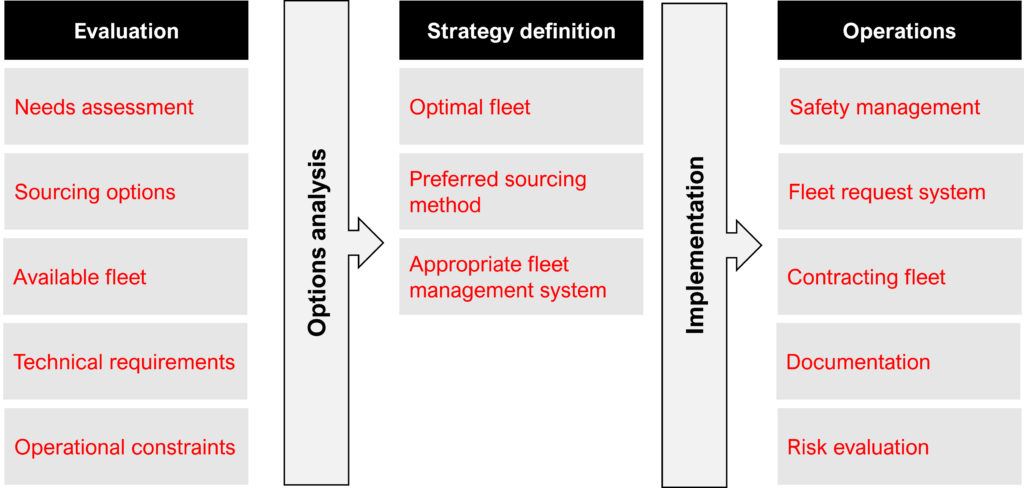

Building a fleet strategy

Learn more in the Defining fleet needs and Resourcing for fleet management sections.

Fleet sourcing: procurement and rental

Learn more in the Resourcing for fleet management section.

Fleet management

Learn more in the Vehicle usage and Managing fleet sections.

Fleet disposal

Learn more in the Fleet disposal options section.

Fleet documentation

Learn more in the Fleet audit trail section.

British Red Cross driving procedure

Learn more in the British Red Cross domestic fleet management systems and procedures section.

Download the whole Fleet chapter here.

There are multiple categories of assets and it is important that assets are grouped in the right category, from the project procurement plan (or handover/donation plan) to the asset register and exit plan of action.

Fleet

- vehicles

- motorbikes

- forklift

- digger

- generators

- solar system set-up.

Communications and IT

- telephones

- smartphones

- satellite phones

- radio sets

- radio base stations

- satellite dish

- handheld GPS

- laptops

- desktops

- printers

- scanners

- CPUs

- digital tablets.

Buildings

- any owned property, built or land

- includes temporary structures such as Rubb Halls.

Household

- office safe

- fridges

- freezers

- cookers

- power stabilisers

- surge protector

- fans

- air conditioning units

- washing machines

- TVs.

Tools

- all tools, powered or mechanical.

Medical equipment

- all specialised equipment

- all assets falling under other categories but used in medical settings should not be classified as medical

- e.g.: a fridge used in a hospital is a household asset, not a medical asset. An oxygen concentrator is a medical asset, however.

Intangible assets

- insurance

- software licenses

- patents.

All above items only count as assets within the following criteria:

> £1,000 OR

> 3 years useful life OR

Powered by electricity or fuel, has a serial number OR

Incurs running cost OR

Defined as an asset by donor

Note: it is good practice to track intangible assets on the asset register. Some donors may require tracking intangible assets.

Read the next section on Items that are not to be managed as assets here.