Assets require more tracking than regular items (see flowchart of definitions). When an asset is received, some of its details must be captured and periodically updated on an asset register. Maintenance services performed on assets must also be kept on file, in order to monitor the usage of the asset.

When assets are issued, the responsibility to maintain them lies with the person to whom they have been issued. When assets are in storage, they are under the responsibility of the asset manager.

Asset transfers must be recorded on asset transfer forms and the assets’ status must be kept updated on the asset register.

The asset register should be used as an asset report and shared with the project team at an agreed frequency (most commonly monthly), but also with donors when they request it and with the finance team when they require information about the value of assets.

Registering assets

When assets are received, an asset folder must be created and references captured on the asset register, so and can easily be traced back.

The asset manager is in charge of tracking the sequence of asset numbers, and of allocating the next available number to the newly received asset following an agreed numbering convention.

Examples of asset numbering conventions:

Name of + Country of use + Asset category + Acquisition year + Sequence number

BDRCS/BANGLADESH/FLEET/2019/22

Or more simply:

Name of NS + Sequence number

BDRCS/22

Note: any numbering convention is acceptable, but it must be used consistently.

The asset number must be captured on the GRN and tagged on the asset as soon as possible.

Make sure that the asset tags used are secure or engrave or paint the asset number on the asset (on generators, vehicles, etc). This becomes the asset’s identification number and must be unique to that asset.

The asset can then be recorded on the asset register, where more details will be listed, such as:

- asset number

- category

- description

- brand/make

- model

- serial number

- budget codes used to purchase the asset (project code), and donor code (where applicable)

- date of purchase

- purchase order reference

- purchase value

- current value (provided by finance)

- GRN reference

- maintenance plan (where relevant – how often does it need to be serviced?)

- person responsible (must match the most recent asset transfer form)

- location (current physical location or point of use)

- status (for example, OK, damaged, in repair, lost, broken or stolen).

All documents related to a single asset must be kept together in an asset file – this can be a plastic file, for example, with a cover sheet listing the documents on file and the date at which they were added.

Documents related to the maintenance, transfer, receipt, insurance, sale and donation of the asset must be kept in that file.

All asset files should be kept together in an asset management folder.

Note: when an asset is received as a donation from a partner, it must be allocated a new asset number and entered on the asset register as a new asset.

For guidance on asset value, refer to the Determining fair market value section of Asset disposal.

Asset responsiblity

Asset responsibility is allocated through an asset receipt form or asset transfer form (both have the same purpose, but the Red Cross Movement generally uses asset transfer forms). Every time the main user of an asset changes, an asset transfer form must be completed and kept on file, and the asset’s status must be updated on the asset register. When the asset transfer form is complete, the user of the asset assumes responsibility for it and their name must be recorded on the asset register as the current user.

When an asset is not allocated to any specific person, it is the responsibility of the asset manager and must be shown as such on the asset register. It is then the asset manager’s responsibility to ensure the asset is stored safely and securely while not in use and that the necessary maintenance services are performed.

The asset manager should have access to a storage space to hold the unallocated assets, which can be anything from a locked cupboard to a storage room. The assets should be stored by category, with their asset tags or markings easy to read while in storage.

Some assets, such as buildings and vehicles, require insurance. Assets must be insured locally unless they are purchased in an organisation that holds global insurance for their assets (always ask your regional logistics coordinator to confirm the status of partners’ asset insurance).

Unless it is a legal or donor requirement, if the insurance cost is higher than the replacement cost (and if this can be shown through quotes), taking out an insurance policy is not mandatory.

Owned buildings, property or land must be captured on the asset register but rented properties may or may not have to be, depending on the duration and financial management of the lease (depreciation can sometimes be applied to long-term rental agreements). Refer to your finance team and/or to the UK-based logistics coordinators to confirm whether a leased building or property should be on the asset register.

Note: some donors may require some categories of assets to be insured. In this case, insurance costs should be covered by the donor requesting the insurance.

Asset checks

Asset checks should be conducted regularly. It is good practice to have five per cent of the asset register, or a minimum of ten assets (whichever is highest) checked against the asset register by finance and logistics staff in each of the country offices on a monthly basis, using the asset spot check form.

All differences must be investigated and reported on the asset spot check form by the staff who conducted the spot check (finance and logistics) and signed:

Locally: by the asset manager’s line manager, programme manager or country manager.

HQ level: by the head of logistics.

The asset spot check form must be signed within a month of being raised, asset checks are required by default, unless otherwise specified in the . The asset spot check form does not need HQ sign-off if it does not identify discrepancies.

A full physical check of all assets must be completed by finance and logistics staff on an annual basis, preferably just before the end of the financial year. All differences must be investigated and reviewed per the same process as for asset spot checks. Following the annual asset check, the asset register must be updated, and the approved investigation report must be attached to the next dissemination of the asset register.

All asset check forms must be kept in the asset management file. The asset manager must keep track of the assets that have been checked during the monthly spot checks to ensure that different assets are checked each month, on a rolling basis.

Following the monthly spot check, the asset register must be updated and the spot check form should be attached to the next dissemination of the asset register.

Reporting on assets

Most donors require regular information about assets purchased with funds they have provided. The details in the asset register should cover all the information they require, but it is good practice to agree beforehand on the information that will be shared.

Whenever new partnerships are designed, it is advisable that the future grant recipient shares their version of an asset register with the donor, to ensure that the level of information is sufficient.

Assets that have not been used for over a year should be reported to senior management by the asset manager, to discuss potentially disposing of them. See the Asset disposal section for more details.

Asset depreciation

The value of assets owned by an organisation sits on its balance sheet. Keeping the balance sheet updated is usually the responsibility of the finance team, but the information required for the process is often shared between logistics and finance. Communication between teams is critical when it comes to recording the right assets at the right value.

In the British Red Cross, see the “Guidance on accounting for fixed assets” (available on Redroom) for information about capitalising assets. Note that in , each team is responsible for their own assets and must maintain an asset register to be shared with the finance team when required (for the end-of-year report for example).

At British Red Cross, assets with a value above £1,000 and with a useful life of more than one year must be capitalised and depreciated. Further details can be found in the policy. Finance should be consulted to understand which assets incur depreciation (not all of them will).

An asset will typically be allocated a life cycle of x years, and its value will decrease by the same amount every year for x years. At the end of x-year life cycle, the asset’s value will be 0. Those 0-value assets still need to be managed as all other assets, and their status must be updated on the asset register.

It is not the responsibility of logistics to apply depreciation to the assets. The asset manager must make sure the depreciated values are computed and shared in due time to report on the total value of assets.

Asset maintenance

Assets that require regular maintenance or inspection services typically include:

- all fleet, including generators and mechanical handling devices (i.e. forklifts)

- buildings, whether owned or rented

- medical equipment

- IT and comms equipment

- some household items.

Regular maintenance

Regular maintenance should be incorporated into the usage cycle of assets. For example, it should be reflected in the fleet plan and the drivers’ allocation plan.

A maintenance planner should be used to visualise all completed, ongoing and upcoming maintenance, and covering all the assets that require maintenance. A maintenance planner is included as a tab in the asset register template. It is important to consider legal requirements that apply to categories of assets: for example, an annual vehicle inspection is required in certain countries, with the renewal of the roadworthiness certificate.

See the Fleet chapter for more details on fleet maintenance and maintenance planning.

See the British Red Cross portable appliances technical guide for details of the maintenance procedures to follow regarding British Red Cross-owned electrical assets in the UK. This guide should inform the maintenance planner for the UK logistics team.

See guideline for maintenance of British Red Cross-owned vehicles in the UK.

Note: Most of the maintenance requirements for buildings in the UK will be covered by British Red Cross’ maintenance service provider. To request a maintenance service, contact , so they can schedule it via the facilities management contractor.

Unplanned maintenance

Unplanned maintenance needs must be identified as such and avoided as far as possible. When they do occur, a maintenance request must be authorised by the asset manager, and the associated costs should be recharged to the budget code of the user requesting the maintenance.

Cost of maintenance

The cost of maintenance associated with an asset should be monitored, with copies of invoices for maintenance services included in the individual asset files kept in the asset management folder.

Looking at the cumulative value of maintenance costs associated to a specific asset can support a decision to dispose of an asset, replace it or to switch to renting rather than owning similar items.

For vehicles, generators and some electrical/medical equipment, maintenance should also be captured in the logbook.

Read the next section on Asset donations here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Assets must be identified as such in the procurement plan and estimated lead times as well as processes (for example, quote-based, national or international tenders) must be defined in the procurement plan, so that the procurement processes can begin in time. If an asset must be procured through an international tender, the delivery lead time will be longer than if it only requires the collection of quotes. The procurement plan should also identify which assets or groups of assets will require procurement waivers, where derogations are required.

Before procuring new assets, make sure there are no existing assets that can fulfil the same role. Sharing assets between projects is a way of achieving value for money, but not all donors will allow it.

Seek advice from your regional logistics coordinator, as they will be aware of the donor requirements and can tell you about assets that could be used for your project (this is particularly true for vehicles).

For details about the different procurement processes and respective requirements, refer to the Procurement chapter.

Read the next section on Registering, tracking and reporting assets, and filing here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Consumables/office supplies

Consumables don’t need to be taken as stock or assets, as their value is usually low. These include cleaning materials, stationery, lightbulbs, and other replacement items.

View and download a diagram illustrating how such items are managed here.

Equipment

Items that are worth less than £1,000, not powered by electricity, do not incur maintenance costs, have a useful life of less than 3 years, and are not defined as assets by the donor who funded their purchase, are classified as equipment and should be tracked on a property register.

Furniture, unless items worth more than £1,000 should be included on the property register rather than on the asset register.

Stocks

For the management of stocks, refer to the Warehousing chapter.

Read the next section on Procuring assets here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

There are multiple categories of assets and it is important that assets are grouped in the right category, from the project procurement plan (or handover/donation plan) to the asset register and exit plan of action.

Fleet

- vehicles

- motorbikes

- forklift

- digger

- generators

- solar system set-up.

Communications and IT

- telephones

- smartphones

- satellite phones

- radio sets

- radio base stations

- satellite dish

- handheld GPS

- laptops

- desktops

- printers

- scanners

- CPUs

- digital tablets.

Buildings

- any owned property, built or land

- includes temporary structures such as Rubb Halls.

Household

- office safe

- fridges

- freezers

- cookers

- power stabilisers

- surge protector

- fans

- air conditioning units

- washing machines

- TVs.

Tools

- all tools, powered or mechanical.

Medical equipment

- all specialised equipment

- all assets falling under other categories but used in medical settings should not be classified as medical

- e.g.: a fridge used in a hospital is a household asset, not a medical asset. An oxygen concentrator is a medical asset, however.

Intangible assets

- insurance

- software licenses

- patents.

All above items only count as assets within the following criteria:

> £1,000 OR

> 3 years useful life OR

Powered by electricity or fuel, has a serial number OR

Incurs running cost OR

Defined as an asset by donor

Note: it is good practice to track intangible assets on the asset register. Some donors may require tracking intangible assets.

Read the next section on Items that are not to be managed as assets here.

Download the full section here.

To determine whether an item procured or received as Gift in Kind is an asset, stock, supply or piece of equipment, consult this diagram.

The below table defines the British Red Cross’ understanding of assets. Different partners may have different definitions (especially around the minimum value or useful life of an item), which will be stated in their own logistics or financial procedures.

| Stock | Office supplies | Equipment | Assets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Consumable items tracked and stored until use/distribution | Temporary or disposable consumables, food or cleaning products for daily use in office or residence | <£1,000 Not powered by electricity No running costs Not defined as asset by donor | >£1,000 or > 3 years useful life or powered by electricity or incurs running cost or defined as asset by donor |

| Examples | Programme supplies for direct distribution Office supplies for distribution to beneficiaries, partners Vehicle spare parts, fuel | Stationary Office cleaning materials Food for office | Furniture Housing equipment Household items | Owned property Vehicles Comms equipment IT hardware Large household appliances |

| Reporting requirements | Stock report | None | Property register | Asset register |

| Storage location | Warehouse | In the office | In use or in storeroom* | In use or in storeroom* |

*The storeroom is typically a small room in the office where a small stock of office supplies is kept.

Available to download here.

In British Red Cross, asset management requirements are defined in the , together with any other specific requirements, whether they come from British Red Cross or from a donor (Section 6 in the standard GAD). Where it has been agreed that the partner will use their own asset management procedure, this requires prior approval and must be mentioned in the GAD.

One person from either logistics or finance must have operational responsibility for asset management, delegated from a country or programme manager.

In certain operations, assets may be managed at a programme or project level, but it is recommended that someone is allocated the task of centralising asset management (see above matrix for reference).

In large, multi-site operations, an asset manager should be hired to ensure compliant asset management. The task of asset management can be part of an existing role, such as logistics officer or finance officer, or exist as a standalone asset manager role.

Read the next section on Categories of assets here.

Download the full section here.

Shipping out the ERU kit

See the ERUs chapter for details on the ERU deployment process.

Shipping RLU stocks

See the RLU stocks chapter for details on shipping globally pre-positioned stocks.

Start reading the next chapter on Assets here.

Monitoring and reporting

In order to understand how your transport strategy serves the delivery of ongoing programmes, it is important to track transport needs, activities and results, and to present them in a structured reporting format, at agreed intervals. Ensuring that all movements are well documented will support the updating of the reports.

A format for monthly logistics activities reporting can be requested from the international logistics team. You may want to adapt it to the specificities of your activities (breaking it down per programme or per destination, for example), but below is a list of performance points that you can track and include in the transport section of the report.

Note that all of the information should be available from either transport documents (waybills, GRNs, claim forms, etc), from organisational information (per diem rates and fuel costs, for example) or from invoices (especially from freight forwarders or clearing agents).

Quantities:

Received

- number of shipments received (for each transport mode)

- total weight and volume of received goods (for each transport mode)

- total number of units (parcels/pallets) received

- ratio of shipments (for each mode of transport).

Shipped

- number of shipments despatched (for each transport mode)

- total weight and volume of dispatched goods (for each transport mode)

- total number of units (parcels/pallets) dispatched

- ratio of shipments (for each mode of transport).

Costs:

Received

- total cost of handling (offloading, reception check and storage).

Shipped

- total cost of handling (loading)

- total cost of rented vehicles

- total cost of use of own vehicles (fuel consumption, driver’s per diem, etc)

- average cost of shipping per kg or ton (for each transport mode).

Lead times:

Received

- average number of days in transit to delivery point (for each transport mode and origin).

Shipped

- average delivery lead time (for each transport mode and origin).

Claims and performance:

Received

- number of claims raised to sender/transporter

- number of unresolved claims with sender/transporter

- OTIF receptions: number of shipments received on time and in full, with no claims raised, for total number of shipments received.

Shipped

- number of claims received

- number of open claims (under investigation)

- OTIF deliveries: number of shipments delivered at destination on time and in full, with no claims received, for total number of shipments dispatched.

International shipments

Received

- number of shipments cleared through customs (for each mode of transport)

- total cost of clearing cargo (for each mode of transport and kg/ton).

Shipped

- number of international shipments despatched (for each mode of transport)

- total cost of international shipments (for each mode of transport).

Optimising transport management

The data presented in the activities report can be used to steer the transport activities towards more efficient use of resource to deliver the needs of programmes.

Data from the report should be shared with other teams, to encourage better use of resources. For example:

- Showing the relationship between better anticipation in order placement and cheaper transportation costs will encourage requestors to place their orders earlier, to save transportation costs.

- Performance data should be shared with service providers to help them focus on necessary improvements.

- Data on cost of freight can be used to benchmark freight forwarders against the average costs of shipping.

- Data on cost of customs clearance can be used to benchmark clearing agents against the average clearing costs.

Organising transport to/from UKO

Read detailed information on organising transport to and from from within the UK and the rest of the world here.

Logistics-owned vehicles

Check with the logistics team if a vehicle is available for quick short-distance, urgent deliveries.

Taxi

Taxis can be arranged for the movement of goods within London – depending on the size of the goods, this can be cheaper than a courier. Taxis (Green Courier) can be booked via the post room up to a week in advance. Cost codes are required, and it is preferred that the post room is approached before last collection at 4pm. Taxi apps have been used in the past (with payment via procurement card).

Read the next section on Shipping ERU kits and RLU stocks here.

Download the full section here.

The air waybill

An air waybill (AWB) is a standard form distributed by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) that accompanies goods shipped by an international air courier to provide information about the shipment and allow it to be tracked. The bill has multiple copies, so that each party involved in the shipment can document it.

An AWB serves as a receipt of goods by an airline (the carrier), as well as a contract of carriage between the shipper and the carrier. It becomes an enforceable contract when the shipper (or shipper’s agent) and carrier (or carrier’s agent) both sign the document.

The AWB contains:

- the shipper’s name and address

- the consignee’s name and address

- the origin airport code

- the destination airport code

- the declared shipment value for customs

- the number of pieces

- the gross weight

- a description of the goods

- any special instructions (e.g., “perishable”)

- the carrier’s terms and conditions and charges.

There are two types of AWBs – an airline-specific one and a neutral one. Each airline’s air waybill must include the carrier’s name, head office address, logo and air waybill number. Neutral air waybills have the same layout and format as airline AWB but aren’t prepopulated.

There are two further types of air waybills: the master AWB and the house AWB.

A master airway bill (MAWB) details the complete information of the consignment, including the place of origin, destination and cost of the shipment. Most importantly, it is issued by the agent on behalf of the airline.

A master air waybill has 11 numbers and comes with eight copies, in varying colours. Since 2010, paper air waybills are no longer required. The ‘e-AWB’ has been in use since 2010 and became the default contract for all air cargo shipments on enabled trade lines in 2019.

A house airway bill (HAWB) is released by a freight agent and serves as proof that the goods have been received by the customer. A HAWB provides two benefits to the customer – it serves as proof of receipt of the goods and is evidence of an agreement between both parties. The HAWB clearly states the terms and conditions and should be read by both parties carefully. Bear in mind that HAWB is not the document title. Most importantly, only one copy of a HAWB is issued, while the airline or the agent releases seven copies of a MAWB (of the total eight copies available).

A HAWB does not have a long verification code like the MAWB ‘s 11-digit code. The first three digits is a prefix, while the rest of the numbers are used to keep track of the consignment.

View and download examples of a Master AWB and House AWB here.

| Master air waybill | House air waybill | |

|---|---|---|

| Issued by | Carrier (e.g. airline, shipping line or groupage service) | Forwarding company (e.g. Kuehne Nagel) |

| Issued on | Carrier's pre-printed air waybill form | Standard air waybill form |

| Signed by | Carrier or their agent | Forwarding agent (carrier not stated) |

| IATA rules | Apply | May or may not apply |

| T&Cs | Carriage T&Cs stated | Forwarder's T&Cs stated |

| References | MAWB number | MAWB & HAWB number |

Available to download here.

The bill of lading

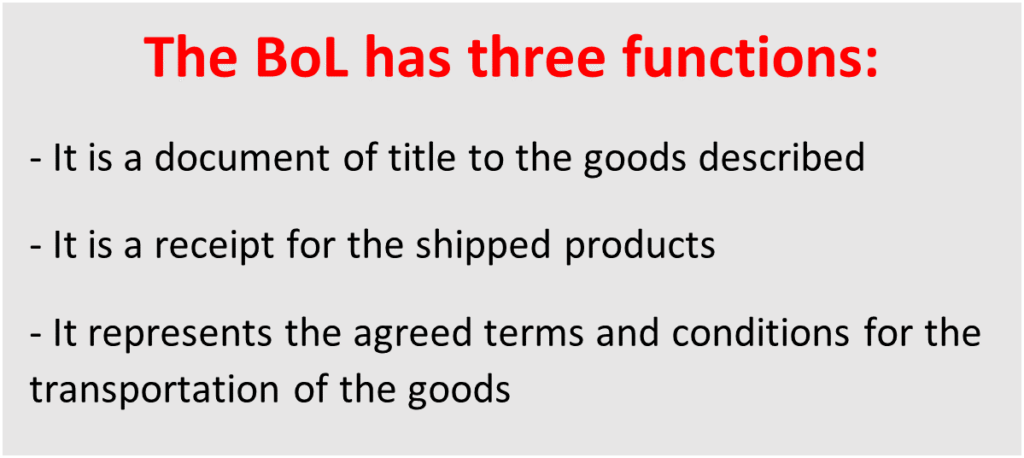

A bill of lading (B/L or BoL) is used for sea shipments.

It is a legal document issued by a carrier to a shipper that details the type, quantity and destination of the goods being carried.

A bill of lading also serves as a shipment receipt when the carrier delivers the goods to a predetermined destination. This document must accompany the shipped products and must be signed by an authorised representative from the carrier, shipper and receiver.

A bill of lading is a legally binding document that provides the carrier and shipper with the necessary details to accurately process a shipment.

BoLs usually carry the name of a specific person (consignee). This is called a “straight bill of lading” and means that the person to whom the shipment is being delivered is the only person who can sign for and accept the shipment. This bill of lading is non-transferrable.

View and download a Bill of lading here.

The waybill

A waybill is an official shipping document that travels with a shipment, identifies its shipper, transporter and consignee, origin and destination, describes the goods and shows their weight and freight. See above for more details on how to use the waybill copies.

The standard IFRC waybill form is available here and at the end of this section.

The CMR

A CMR is a waybill used in international road transportation. It is an abbreviation of a French term: “Convention relative au contrat de transport international de marchandises par route”.

If goods are being transported internationally by road within the European Economic Area, you must use a CMR note. At least three original copies are required, which are signed by both the freight carrier and the sender.

See link for members of the CMR convention – shipments by road from Europe to these countries (and back) require CMR letters. The CMR forms a contract between the sender and the carrier company and confirms that the carrier has received the goods. It also sets out the transport and liability conditions between the two parties.

The following details are part of the CMR waybill:

- place and date of issue

- address and name of sender

- address and name of carrier

- place and date of acquisition of the goods, and place of delivery

- name and address of recipient

- definition of the type of goods, as well as the type of packaging

- the quantity and sequence of the packages (“box 1 of 22” for example)

- the weight and dimensions of each box

- statement of costs (for example, for freight, tariffs, extra charges, etc)

- instructions for handling tariffs, and for other official regulations

- the agreement that all transports must conform to conventions, even if contents differ

- mention of the prohibition of transhipment

- the costs carried by the sender

- the collection fees at delivery

- exact information about the value of the transport goods

- all handling specifications from the sender to the carrier, for insurance

- the time limit by which the transport must be completed

- a list of all documents handed to the carrier.

The colour-coding and disposal of the CMR consignment not is explained here.

Read the next section on Transport data analysis here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download the full section here.

Whenever vehicles are used to transport goods belonging to the Red Cross Movement, it is strictly forbidden to transport:

- weapons of any sort

- any personal items or other freight not directly related to the operation requiring transport services

- people, be they Red Cross personnel, military, or beneficiaries. An exception would be providing urgent transport to the nearest medical facility, but this must, as far as possible, be agreed with a security or fleet manager beforehand and captured in an incident report upon return.

Any observed breach of these rules must be immediately reported in an incident report.

Reporting incidents

All incidents involving British Red Cross staff or property must be reported – refer to the British Red Cross or applicable National Society’s incident reporting procedure for information on how to do this.

Where British Red Cross delegates are seconded into another organisation such as the or , or where they are working under the umbrella of another organisation such as a , this organisation’s incident reporting procedure must also be followed, in parallel to that of British Red Cross.

Use of military transport means

As per the Movement guidelines on the use of military and civil defense assets (MCDA) in disaster relief:

“Military assets should only be used as a last resort, where there is no civilian alternative and only the use of military assets can meet a critical humanitarian need.”

No armed escort is allowed for shipments undertaken for the Red Cross Movement, unless:

- There is extremely pressing need (e.g., to save lives on a large scale).

- It represents no added security risk to beneficiaries.

- No one else can meet the needs.

- Armed protection is for deterrence and not firepower.

- Parties controlling the territory are in full agreement with armed escort.

- Protection against bandits/criminals is needed.

- Authorisation is given in advance, at the specified level – typically secretary general or senior director within the HNS and ICRC/IFRC in Geneva.

All military actors run the risk of not being perceived as neutral and jeopardising the Red Cross Movement’s commitment to neutrality and impartiality. Absolute rules in terms of using military resources are:

- Never use armed military transports.

- Never use the assets of a party involved in an armed conflict.

- Never use military assets simply because they are available.

Use of the RC emblem on transport not owned by Red Cross

Red Cross-owned fleet will always bear a Red Cross emblem. The decision on which emblem (, , British Red Cross or ) to use will be made in discussion with the lead Red Cross Movement partner and the HNS – this applies to both Red Cross-owned and Red Cross-rented vehicles.

Where fleet is rented, the emblem must be clearly visible on the rented vehicle (truck, small vehicle, boat, or plane).

On road vehicles, flags should be used at the front of the vehicle. The emblem, in whatever form, must be removed and retained by the Red Cross logistics or transport manager immediately after the vehicle is no longer serving the Movement.

Based on the above conditions, where the Red Cross agree to use military assets for transportation, vehicles must visibly carry the emblem.

Read the next section on Transport documentation here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here

Download full section here.

Some consignments are more sensitive than others. Typically, the transportation of dangerous goods or cold chain items require stricter preparation and tracking.

Cold chain shipments

When transporting cold chain items, remember to:

- Double check the cold chain capacity calculations: are you sure that the temperature can be maintained for the duration of the shipment?

If not, make sure you include additional icepacks to the consignment, include them on the packing list and waybill, and provide the transporter with instructions as to when and how they must be used. - Include a temperature tracker in the consignment. You can usually arrange for shippers to fit a tracker in a container (at a cost).

Where you are the shipper of goods, you can procure temperature trackers to include in boxes, and provide the receiver of the goods with means to read the trackers once goods are delivered. - Follow up on any cold chain rupture claims notified by the consignee and implement corrective actions.

Transporting dangerous goods

There are nine classes of dangerous goods. Find more information on dangerous goods here.

Transportation of dangerous goods is highly regulated and should ideally be handled by a third-party service provider. Freight forwarders usually have capacity to advise on dangerous goods shipments and may have to pick them up from your warehouse to arrange for special packaging prior to the shipment.

Drop-ships

Drop-ships are cases where a supplier might deliver to the end user directly, upon specific request of the buyer. The buyer can be the consignee or a service provider acting on behalf of the consignee (a regional logistics hub, for example, in the context of the Red Cross Movement).

In drop-ships, the supplier will usually present at the delivery place with a waybill of their own format and/or an internal delivery note. In this case:

- Sign the waybill only when all packaging units have been accounted for (pallets, boxes or loose cargo).

- Sign the delivery note when all the items on the packing list have been delivered. The transporter should leave a copy of the signed delivery note with the person who signed it.

- Raise a claims form where there is any discrepancy.

- Raise a GRN to record entry into stock.

- Move the goods to the bulk storage area or proceed to distribution if the goods have been delivered at the point of usage.

- Update stock records if goods enter the warehouse.

- Inform the sender (supplier or third party, such as ) that goods have been received. Send copies of waybill, delivery note and claims form.

If drop-shipped goods are distributed immediately, they do not need to be recorded in stock. A delivery note is enough to reconcile with the order or requisition.

Deliveries at point of usage

Where requested goods are delivered at the point of usage or distribution, a delivery note is preferable to a GRN, as the items are not to be managed by logistics. That way, the items do not become Red Cross stock, but the delivery is still documented. A copy of the delivery note must be kept in the procurement file before it is transmitted to finance for payment.

Read the next section on Safety, security and incident reports here.

Related resources

Download useful tools and templates here